Toxic Traditions: DDT and How History Repeats Itself with Chemical Pollution

“But man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.” – Rachel Carson, Silent Spring

Ospreys (Pandion haliaetus) by Steve Gorin, NCWF Photo Contest Submission

In 1960 in the Amazon basin, along the coast of Guyana, a female osprey takes her final flight from her winter roost in a mangrove tree. Today – along with thousands of other members of her species – she begins her long, nearly 3,000-mile solo journey back to her summer home.

There, she reunites with her mate of two years. As they do each season, the pair engage in the intricate courtship ritual of mating ospreys. After several weeks, they have successfully mated, and together, they begin their nesting season atop a towering pine on the shore of a familiar lake. Three days later, she lays her first egg.

As she lays, her mate roosts nearby, scanning the horizon for threats. He prepares for his role – hunting and bringing back fish from the lake to sustain their growing family.

The next day, she lays another egg. And then another. At last, her clutch is complete. As she settles atop her clutch, an unsettling crack cuts through the quiet morning. One of the eggs gives way under her weight. She shifts uneasily, but it’s too late—another cracks, then another. The shells are far too thin to withstand incubation.

Thousands of miles traveled, many hours of courtship rituals and meticulous nest building, and the patient labor to produce a clutch of eggs that would never hatch… all of it falls through the cracks of her nest.

This was the heartbreaking reality for many ospreys, eagles, falcons, and other birds of prey during the 1960s and ’70s. The devastating culprit? Chemical pollution.

DDT: The “Miracle” Pesticide with a Dark Side

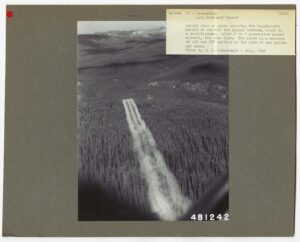

Photo: USDA Forest Service and National Archives and Records Administration

DDT, short for dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, was once widely used as a pesticide in the United States and beyond. Initially developed in the late 19th century, its insecticidal properties weren’t discovered until 1939 by Swiss chemist Paul Hermann Müller, who later won a Nobel Prize for his work.

During World War II, the military used DDT to control insect-borne diseases like malaria and typhus among soldiers and civilians. It was sprayed over vast areas to kill disease-carrying mosquitoes and lice, proving so effective that it was hailed as a life-saving breakthrough. After the war, DDT became a staple in commercial agriculture, used extensively on crops to protect the booming industry. It was also widely applied in residential areas, with homeowners and public health officials using it to combat everything from mosquitoes to garden pests.

At just $0.25 per pound, DDT was both inexpensive and highly effective – seemingly a miracle chemical, especially given its role in preventing crop devastation, boosting agricultural profits, and controlling deadly diseases. By the 1950s, its use was ubiquitous, with aerial spraying campaigns, household applications, and large-scale distribution across farmlands, neighborhoods, and public spaces.

However, this so-called miracle had a dark side, and it took just one person to bring its dangers to light.

Rachel Carson and Silent Spring

Rachel Carson (Photo from USFWS)

Rachel Carson, an aquatic biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) from 1936 to 1952, became increasingly concerned about the harmful effects of pesticides. As reports of mass bird die-offs and environmental contamination surfaced, she realized that the widespread use of DDT, and its long-term consequences, had not been fully studied. When DDT was introduced for civilian use in 1945, her concerns deepened.

She initially attempted to publish an article on DDT’s dangers for Reader’s Digest, but it was rejected. For years, her warnings went largely ignored. It wasn’t until the early 1960s that people began to listen. Carson published a series of essays in The New Yorker, which later became Silent Spring—the groundbreaking book that played a significant part in igniting the modern environmental movement.

Carson laid out the facts: DDT was a harbinger of death. She focused on its devastating impact on birds, using the book’s title to symbolize a future where spring would be eerily silent, empty of birdsong. She described how DDT was applied to landscapes, only to wash into waterways, where fish, amphibians, and other organisms absorbed the chemical. Through bioaccumulation, the toxic compound built up in the tissues of small organisms, and through biomagnification, its effects intensified as it moved up the food chain.

For fish-eating birds of prey—such as ospreys, bald eagles, and peregrine falcons—this was disastrous. The chemical interfered with calcium metabolism, leading to eggshells so thin that they cracked under the weight of incubation. Populations plummeted as reproductive failure spread across multiple bird species. According to historian Dan Flores, though nobody knows an actual figure, the some 100,000 bald eagles that were present in the U.S. in the 1800s had dwindled to an estimated 487 nesting pairs by the time of a 1963 census.

But DDT didn’t just harm wildlife—it harmed humans too.

The Human Cost of DDT

Tanker truck loaded with DDT in 1974.

Photo: USDA Forest Service, Region 6, State and Private Forestry, Forest Health Protection.

DDT accumulates in fatty tissues, meaning that once it enters the body, it lingers. Studies found traces of DDT and its breakdown products in human blood, with particularly high levels detected in the breast milk of nursing mothers. The chemical was so pervasive that nearly every American in the mid-20th century had some level of DDT in their system.

Over time, research linked DDT exposure to a range of health concerns, including nervous system damage, reproductive issues, liver problems, and an increased risk of cancer. Some studies suggested a possible connection between DDT and breast cancer, while others raised alarms about its role as an endocrine disruptor, interfering with hormone function. While scientists debated the full extent of its dangers, the evidence was concerning enough to prompt government investigations.

After three years of review, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) banned DDT’s general use in 1972, marking a major victory for environmental and public health advocates.

The Lingering Impact

Although DDT has not been widely used in the U.S. for over 50 years, its persistence in the environment remains a concern. Unlike many chemicals that break down quickly, DDT binds to soil particles and accumulates in plant matter, lingering for decades. Even today, trace amounts can still be detected in the environment, particularly in sediment-rich areas and older agricultural sites.

While bird populations have made a remarkable recovery—thanks in part to the banning of DDT and conservation efforts—its legacy serves as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of chemical use.

Moving Forward

Many might argue that society has moved past DDT and its harmful effects—and to some extent, that’s true. But history tells a different story. Time and again, we have phased out one dangerous chemical only to replace it with another.

We’ve seen this cycle repeated with lead in gasoline, “forever chemicals” (PFAS) in consumer products, neonicotinoid pesticides harming pollinators, and other industrial compounds that were once deemed safe but later revealed to have devastating consequences. In some cases, science simply takes time to uncover the long-term dangers of certain chemicals. In others, industrial progress prioritizes convenience and profit over safety, operating under a mindset where the ends justify the means.

If we want a future where both humans and wildlife thrive, we must take a more critical approach to chemical management. This doesn’t mean rejecting chemicals outright—it means being more proactive and thorough in studying their effects before they become widespread. And if we choose to use them, we must develop strategies to mitigate their impact, ensuring they serve the greater good without causing lasting harm.

You can learn more about the toxic substances and pollutants that currently pose major threats to wildlife and people and how you can help mitigate those impacts in our blog post: Silent Killers – 10 Pollutants That Pose Harm to Wildlife.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources