Fireworks Fallout: The Unseen Toll of Fireworks on Wildlife

They usher in the new year, provide a grand finale for sports games, and – perhaps most relevant to this time of year – are emblematic of our country’s celebration of independence.

Fireworks have been a prominent feature of human cultures for millenia, with the first “fireworks” being invented in the second century BC in ancient China. This creation likely came in the form of people throwing enclosed sections of bamboo into fire, causing air pockets within the bamboo segments to expand and explode – resulting in something very much like the firecrackers we are familiar with today.

However, these early bamboo “fireworks” are a far cry from today’s grand displays of color erupting and showering down from hundreds of feet in the air.

Undoubtedly, fireworks are a breathtaking spectacle. But they are not without their downsides. Each year, more studies emerge on the impact firework fumes and chemicals have on human health. Not to mention that firework shows generally take place well after sunset – much to the chagrin of anxious pet owners and parents of young children.

But perhaps one of the most overlooked impacts of fireworks is how they may affect wildlife.

Fireworks in North Carolina

Particularly around the holidays, fireworks are a common sight across the country. Massachusetts is the only state that all-out bans the shooting of fireworks… though they do allow select fireworks shows put on by professionals.

In North Carolina it is illegal to purchase any large scale fireworks, though sparklers, snakes, poppers, and other small scale pyrotechnics are legal. Other fireworks may be obtained with authorized pyrotechnic licensing through the state. Even with these regulations in place, many North Carolinians travel out of state to obtain larger fireworks to deploy back at home in North Carolina.

Despite regulations varying by state, the firework industry is robust to say the least, and has only increased in recent years. In 2022, $2.3 billion was spent on consumer fireworks, and $400 million on display fireworks. This translates to 461.7 million pounds of fireworks in 2022 alone (McCarthy, 2023).

Needless to say, the shooting of nearly 500 million pounds of paper, plastic, and ignited black powder into the air does not come without some level of environmental impact. And when such impacts are made on the environment, wildlife is negatively impacted as well.

So, what are the potential negative effects of fireworks to wildlife?

Fireworks and Disruption of Wildlife Patterns

Typically, animals adhere to familiar patterns within their environment.. However, on occasional days throughout the year, the night sky is disrupted by explosive sounds and multicolored flashes of light. While we may anticipate these events, wildlife do not. At best, this places stress on wildlife and, at worst, it can result in mortality.

Migratory birds – including geese – are adversely impacted by fireworks

The sudden light and noise has the potential to startle many species, particularly nesting birds, which may cause the birds to fly into dangerous locations such as roadways, or even cause them to collide with trees or man made structures in the dark. While most studies and reports on how fireworks impact wildlife centers around birds, other species may be similarly affected by such disturbance.

A fireworks study conducted on geese in Europe on New Year’s Eve demonstrated that geese near developed areas were startled from their nesting sites by fireworks, resulting in sudden flight away from these areas, decreased sleep hours, and substantially more flight miles than they would have taken on nights without fireworks. But the impacts of these events were not isolated to the night of the firework event. According to the study, the geese “spent more time foraging and never returned to their original sleeping sites” (Kölzsch, 2022).

Another study in the Netherlands using an operational weather radar recorded that on New Year’s Eve, thousands of birds were startled into flight at and after midnight, with peak flight densities maintained for 45 minutes and at heights of 500 meters. The study also noted that the highest densities of birds startled into flight by the fireworks were over grasslands and wetlands, including nature conservation sites that these species use as refuge for rest and feeding (Shamoun-Baranes et al., 2011).

One catastrophic example of the impact fireworks can have on migratory birds came in the form of a massive red-wing blackbird die-off in Arkansas in 2010. Following a New Year’s Eve fireworks display, over 5,000 birds fell from the sky after colliding with obstacles. Reportedly, city residents said the event caused many to fear an apocalyptic event (Opar, 2011).

Chemical and Pollution Impact of Fireworks

As noted above, fireworks have an immediate impact on wildlife, but these impacts may last well after the event, in the form of chemicals and pollutants.

Fireworks are generally constructed from paper, plastic, and black powder. When they erupt, these materials do not dissolve harmlessly into the atmosphere. The paper and plastic casings and packaging fall back to the ground and are often not retrieved by spectators, resulting in widely distributed litter that pollutes a variety of wildlife habitats. Additionally, the explosion of these casing materials introduces microplastics to waterways, harming humans and wildlife alike (Han, 2023).

But the black powder itself – composed of potassium nitrate (saltpeter), sulfur, and charcoal – causes issues of its own. Traces of heavy metals including copper, lead, titanium, and strontium (USGS) have been found in fireworks, along with harmful toxins including ozone, sulfur dioxide and nitric oxide (NYU Langone Health). When made airborne, these chemicals find their way into the air and waterways.

Though studies have not been conducted on the impact of these chemicals on wildlife, these elements are thought to be as harmful to wildlife as they are to humans, particularly in causing respiratory and cardiovascular diseases.

Fire Hazards of Fireworks

Another threat to wildlife posed by fireworks lies in the name itself. Whether implemented correctly or incorrectly, fireworks by nature pose a risk of starting unintended fires on the landscape.

Whether by falling detritus still on fire, or direct and irresponsible use of fireworks, leaf litter and grass may ignite and fires may quickly grow out of control. These fires not only risk killing wildlife directly, they also destroy habitat and displace wildlife, and may force animals to flee into dangerous areas such as roadways.

Alternatives and Ethical Fireworks Handling

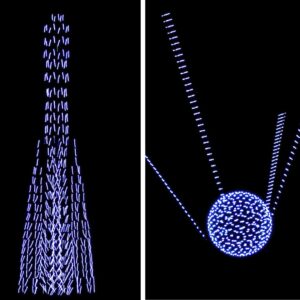

Drone light shows offer a lower-impact alternative to fireworks displays

To protect North Carolina wildlife and their habitats, we need to be mindful of when and how we use fireworks. The most effective way to reduce the disturbances and pollution caused by fireworks is to avoid using them entirely. However, opting for smaller firework displays instead of the larger scale shows can help mitigate negative effects.

Additionally, city and event planners may consider alternatives such as drone light shows to replace the use of fireworks. Since their inception in the early 2010’s, drone light shows have become increasingly popular due to their comparable safety and reduced environmental impact. These displays feature multiple unmanned aerial vehicles choreographed to fly in intricate patterns, creating shapes and figures that traditional fireworks cannot achieve. As their popularity grows, many companies now offer drone light shows for holiday celebrations, directly competing with traditional fireworks.

Considering alternatives to traditional fireworks shows presents a unique opportunity to exercise creativity around the expression of our holiday celebrations.

However, if you still intend to have a fireworks display of your own, remember to keep in mind the impact that it has on wildlife and the habitat. Take time to consider your location and ensure that you are not at risk of starting fires or disrupting any known wildlife in the area. After the event, remember to remove any litter left behind to diminish any potential impact to wildlife.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Sterling McDonald, NCWF Communications Intern

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources