Looking Up: NCWF Scholarship Winner Michelle Kirchner, Rare Ants, and Tree Canopy Ecology

Photo Credit: Michelle Jewell

Climbing trees is a uniquely exploratory activity, one that many of us learned to appreciate during the outdoor adventuring of childhood. All it took was a branch close enough to the ground to begin the ascent, and then it was climbing hand over hand, limb above limb… in search of a vantage point, one that provided not only a more expansive view of the world below but also illuminated a completely different world. An entire world in the treetops.

While perhaps rooted in that same excitement of adventure into the unknown, the type of tree climbing that Michelle Kirchner does is a bit different than the quick childhood foray up into the branches of a young beech or maple tree. Rather, her journey started while she was suspended from climbing ropes in the high canopy of a forest in Madagascar. Fully immersed in this island forest ecosystem, she and her colleagues were there in search of one particular piece of that ecosystem: ants.

It was while searching for ants in these Madagascar tree canopies that Michelle first thought, “Alright… ants live in the canopy here. That’s kind of cool. But what’s at home?”

So began her journey into the treetops of North Carolina, in search of the ants that fill this unique and underexplored ecological niche, the temperate North Carolina overstory.

From Madagascar Dry Forests to North Carolina Public Lands

Photo Credit: Michelle Jewell

Michelle Kirchner is a PhD candidate in the Department of Applied Ecology and the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology at NC State University. Though her area of study now rests solidly in North Carolina treetop ecosystems, that was not the beginning of her journey into the canopy. That started five years ago, 9,000 miles south of North Carolina.

In 2019, Michelle was part of a month-long NSF-funded Ants in the Canopy Bootcamp in Madagascar, where she spent a week learning to climb trees from professionals before using the following weeks to explore the canopy, analyze their findings, and catalog the collected data.

As she was exploring the treetops of Madagascar, she thought about the forests in her home state of North Carolina and what ant species might be found there, if someone were to venture into the tree canopy.

“The more I looked into it, the more I realized that we really don’t have much of an idea of what’s going on up there,” Michelle said. “But after learning and training in Madagascar, I was like ‘Okay, I have the skills to actually answer that question now’.”

So began her journey from the dry forests of Madagascar to the public lands of North Carolina, where she returned to the treetops. Little did she know that a rarely observed wildlife species, a pandemic, a scholarship award, and scientific sabotage via coyote, would all be waiting for her in the forests of NC.

Trials in the Trees

Photo Credit: Michelle Kirchner

Michelle was awarded a North Carolina Wildlife Federation scholarship to aid in her research around ants – particularly arboreal or semi-arboreal ants. She used the money towards thermocouples, precise thermometers that she used to read the inside temperature of ant nests both in the canopy and on the ground. These readings can provide insight into what actual thermal environment these ants are experiencing and how different that environment is on the ground versus in the canopy. With these and other pieces of research technology in hand, she was prepared to begin a complex study of treetop ecosystems across the state.

“I originally had this very elaborate plan to do a gradient of diversity and ecology across all the ecoregions in North Carolina, because it kind of spans this elevational and climatic gradient that I was interested in exploring. I wanted to get an idea of how diversity might change along that gradient,” Michelle said. “But of course, my first field season was supposed to start in 2020, and that’s when the pandemic hit.”

The COVID-19 pandemic derailed academia and scientific research in many ways, particularly for those researchers who required travel to conduct studies. Without the ability to take overnight road trips, Michelle’s elaborate, state-wide plans were compromised.

More than that, social distancing limited her ability to take trips out into the field with colleagues, which is crucial for safe and effective tree climbing and arboreal research. All of this forced her to make some hard decisions both about her study area and her research methodology.

“I had to shrink down everything to the Piedmont region, where I could just take day trips out into the field,” Michelle said. “But ultimately, that led me to stay more local and focus on specific locations for years. So I’ve been able to kind of dig in deeper to the ecology of the system.”

For Michelle, these areas of focus were Butner Falls of Neuse Game Lands, Eno River State Park and Umstead State Park. She narrowed her study to the four of the most common tree species found in the Piedmont region: loblolly pines, white oaks, sweetgum, and red maples.

“Most of the time, when people say they’re sampling for arboreal species in temperate systems, they’re just putting bait on the tree trunk two meters off the ground and they say ‘Okay, that’s arboreal, because it’s on the tree’,” Michelle laughed. “But I was like ‘Well… is that arboreal?

Photo Credit: Michelle Kirchner

I’d rather get up into the canopy to be able to know for sure that I’m actually getting treetop species.’”

But without colleagues to help her climb, Michelle had to exercise ingenuity in her data-gathering methods. That meant having to find a way to sample from the canopy while keeping her feet on the ground – so she invented an apparatus that allowed her to do just that.

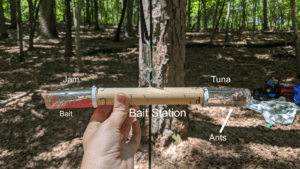

This apparatus is a baiting system using a wooden dowel with two containers of bait (one filled with fruit jam, the other filled with tuna fish) on each end, all fixed to a long strand of parachute cord, hanging in the tree canopy. Using a specialized slingshot, she launched a weighted beanbag up over the highest branches of the

study trees and hoisted the bait station up to entice the ant species present in the canopy.

After letting the bait sit for four hours, she would return and lower the bait, inspecting and collecting the ant species gathered on both the sugar-dense jam bait and the protein-dense tuna

Specialized slingshot for bait placement.

Photo Credit: Sarah Ferritter

bait. The exercise was effective and provided insight into what food sources the ants in the canopy were seeking… but these tests did not go without mishaps.

Several times, Michelle returned to her testing sites to find her parachute cord cut by a knife and her baits destroyed. Another time, she arrived to find her materials torn to shreds, but not by human hands.

“Coyotes came and chewed everything to pieces,” she said. “They had pulled out our thermocouple temperature sensors, which were just covered in teeth marks… but that’s part of fieldwork, sometimes your stuff just gets eaten by coyotes.”

Despite these interruptions, she was able to gather good data from her baiting technique. But to get a holistic picture, Michelle knew that she had to get into the treetop herself. Her opportunity came in 2021, when she made her biggest discovery up to that point.

Treetop Discoveries

Michelle focused her research area on oak trees – particularly white oaks – exercising the tree climbing skills she learned in Madagascar. Climbing into the crowns of these stout and branching oaks, she closely observed the branches and peeled back flakes of bark in search of ant species of interest. While poking and prodding the branches, she often came across some startling surprises.

“There are lots of centipedes up there,” Michelle said. “When I open up branches they just come jumping out at me. I hate it every single time. There’s tons of pretty huge fishing spiders up there, too.”

But these are not the only things she found in the tops of the oaks – and one particular encounter with some unfamiliar ants particularly caught her attention.

“I found this dead branch up in the top of one of the oaks and cracked it open – and there was an ant colony in there. And I thought ‘Wait a minute… are these what I think they are?’ I wasn’t sure, but I knew they were weird. I knew it was exciting.”

Upon later examination of the colony, it was revealed that the colony Michelle found belonged to Aphaenogaster mariae, a rarely observed species of arboreal ant that nests exclusively in treetop canopies.

Aphaenogaster mariae is probably a parasitic ant species, relying on existing ant nests and colonies that the Aphaenogaster queen can infiltrate and take the place of the existing queen, producing a pheromone that gets the parasitized colony to care for her and her brood, as the new queen.

While the species had been previously observed a couple of times in North Carolina, this was the first time that a full colony including males had been discovered and recorded. But while the species is rarely sighted, Michelle believes that they may not be as rare as people think.

“It’s very localized,” Michelle said. “So in the places where it exists, it probably exists at a fairly normal density. But it requires the existence of established ant colonies to parasitize. And even when it is established, people don’t often notice it because it’s in the treetops.”

Treetop fishing spider.

Photo Credit: Michelle Kirchner

This idea that entire webs of life – including rarely observed ant species – exist in the overstory above our heads is not a new one, but it is a concept still relatively untapped by the study of ecology, particularly in temperate climates. According to Michelle, as a state with a temperate climate, it is generally assumed that there are almost no species in North Carolina that are specialized to treetop ecosystems. Rather, many believe that species that are present in the treetops here must frequently move between the forest floor and the treetops to maximize access to resources.

“We can’t just assume that there’s nothing going on up there,” Michelle said. “I think my work addresses the fact that we can’t just make those assumptions. That being said, there are plenty of ground species that utilize the canopy.”

Michelle says that a third of the Piedmont forest ant biomass uses the canopy as a resource. But her ventures into the treetops have unveiled more than ants; many other species also utilize treetop habitats. She excitedly recounts her encounters with treetop pollinators, skinks, summer tanagers, and bald eagles… and an “alarming” amount of slugs.

But an especially notable and puzzling encounter was with a small rat snake, a little higher than most would expect.

Treetop rat snake. Photo Credit: Michelle Kirchner

“I was like 18 to 20 meters up in a tree. I looked down on the branch below me and there was this baby rat snake curled up in one of the dead branches.” Michelle said, “I was like “What are you doing here?” and it was looking back at me like ‘What are YOU doing here?’ ”

These encounters have impressed upon her the critical importance of the treetop ecosystem, a conviction she hopes to communicate through her research.

“What I really love about this work is that I’m getting to think about the ecology of my backyard, of my community. Because these are the trees that we all just drive past, you know?” Michelle said. “There’s so much attention around the tropical Amazonian tree canopy and charismatic places like that. But I think it’s different when these are the types of ants that live in your trees – not in the Amazon but just off Old Creedmoor Road. I love that, and I love the idea of trying to understand more about the world that we live in and how we’re changing it. But also how nature adapts to that change.”

Michelle hopes that her research will play a part in incorporating the canopy ecology of temperate systems into the overall understanding of how forest ecology works. She says this has implications for how forests should be managed amid urbanization and climate change. In addition to that, it has implications for the species that call the overstory home.

“There’s an entire ecology up there, of plants and animals,” Michelle said, “There’s an entire world up there that’s only a few meters above our heads. But we just don’t think about it… unless we’re looking up there.”

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager