For the Love of Birds: Six Birds from North Carolina’s list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need

Donate To The Birds This Giving Tuesday

Birds have always fascinated us.

Two of the oldest expressions of this fascination are a 40,000-year-old cave painting of giant birds in Australia and a 33,000-year-old bird figurine from Germany, carved from mammoth ivory. The purpose behind these early artistic creations remains uncertain, but they reveal a deep appreciation for the importance and beauty of birds in ancient cultures – an alignment of identity between humans and the creatures they so carefully observed, a reflection of daily life, and a celebration of spirituality.

This enduring connection continues today. Nearly 96 million Americans – three in ten – participate in birdwatching each year, captivated by the color, song, and movement of the birds around them. Aldo Leopold captured this wonder when he wrote, “Whereas I write a poem by dint of mighty cerebration, the yellow-leg walks a better one just by lifting his foot.”

Perhaps what most firmly roots birds in our shared culture is their constant presence – their tendency to be seen and heard wherever we are. Yet their absence has also helped shaped the modern conservation movement. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring drew its haunting title from the imagined stillness of a world without birdsong.

Theodore Roosevelt once wrote to ornithologist Frank Michler Chapman about the disappearance of bluebirds in his region after harsh winters, saying, “The loss was like the loss of an old friend, or at least like the burning down of a familiar and dearly loved house.” Speaking of the extinction of the Carolina parakeet and passenger pigeon, he lamented that their loss was “as severe as if the Catskills or the Palisades were taken away,” comparing the silence left behind to the disappearance of the works of ancient philosophers like Polybius and Livy.

In a very real sense – as these reflections show – the presence of birds, and the fear of losing them, have long united us. Yet in just the past half-century, North America’s bird populations have declined by nearly three billion – a staggering 29% drop since the decade of Silent Spring. Much of that loss is concentrated among familiar families: sparrows, warblers, blackbirds, and finches.

Today, we must summon the same appreciation, respect, and conviction that have always bound us to birds to ensure that they remain with us. While a world entirely without birds may be unlikely, it is possible that we could lose species that have shared the earth with us for millennia – some even older than humankind itself. Without concerted effort, the arrival of spring could grow quieter still.

In this blog, we embark on a journey to explore a selection of bird species on North Carolina’s list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need. Through understanding and appreciation, we hope to foster a collective commitment to preserving these feathered ambassadors of our state’s diverse ecosystems.

This Giving Tuesday, you can make a difference for North Carolina’s birds. From cardinals to painted buntings, your gift will restore habitats and strengthen conservation efforts—and thanks to NCWF’s Board of Directors, every dollar will be matched 1:1, up to $40,000! Double your impact for the birds that call North Carolina home.

Brown Pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis):

NC Range: Coastal

The brown pelican, though one of the smaller pelican species, still ranks among the larger coastal North Carolina seabirds with a length ranging between three to five feet and a wingspan exceeding six and a half feet.

The brown pelican, though one of the smaller pelican species, still ranks among the larger coastal North Carolina seabirds with a length ranging between three to five feet and a wingspan exceeding six and a half feet.

These social birds prefer the company of their kind for both breeding and feeding, forming colonies of thousands in island and coastal regions. While generally migratory and drawn towards warm coastal areas for nesting, some birds become year-round residents, risking frostbite on their webbed feet and throat pouches during colder months. When engaging in dispersing behavior, brown pelicans move away from their birth congregation to join a separate breeding congregation, enhancing genetic diversity.

Strictly marine, brown pelicans stick to coastal waterways, avoiding venturing too far out to sea, typically staying within 20 miles of the coast. Their colonies shift frequently, yet they nest in safe locations like secluded islands, sand dunes’ vegetation, or on cliffs. Breeding occurs once a year, usually around April, resulting in a brood of two to four eggs.

Piscivorous by nature, brown pelicans feed almost exclusively on fish, including anchovies crucial for regurgitation during nesting. Unlike other pelicans, they dive from the air for fish, distinguishing them from their sister species, the Peruvian pelican. While adult predation is rare, eggs and hatchlings face threats from gulls, raptors, alligators, feral dogs and cats, raccoons, and fire ants. Parasite infestations afflict adult pelicans due to their fish-based diet.

The brown pelican population saw a decline in the 1940s due to the widespread use of dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane (DDT; a synthetic insecticide), thinning eggshells and rendering young inviable. Listed under the ESA from 1970 to 2009, a ban on DDT and reintroduction efforts led to population growth, removing brown pelicans from the endangered species list. Despite this progress, coastal pollution, including oil spills and fishing litter, poses a threat. NCWRC protects nesting sites to prevent tampering and destruction by both humans and predators.

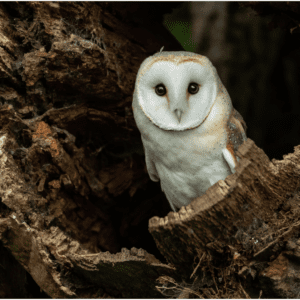

Barn Owls (Tyto alba):

NC Range: All Regions

Barn owls are among the smaller owl species in North Carolina and display a distinctive appearance with a white face and belly complemented by golden brown anterior feathers. Unlike the familiar hoot of many owls, barn owls produce a sharp, screeching sound.

Barn owls are among the smaller owl species in North Carolina and display a distinctive appearance with a white face and belly complemented by golden brown anterior feathers. Unlike the familiar hoot of many owls, barn owls produce a sharp, screeching sound.

Operating as nocturnal birds of prey, barn owls, similar to other owl species, primarily target small rodents for their meals. In contrast to owls residing in wooded areas, barn owls prefer flying and hunting near the ground, often hovering above agricultural fields and small clearings.

As cavity nesters, barn owls frequently choose old barns and vacant buildings for nesting, contributing to their name. When such structures are unavailable, they opt for tree cavities. Forming lifelong pairs, barn owl couples typically generate one to three sets of eggs annually, ranging from 2 to 18 eggs in each clutch.

Young owls face predation from raccoons and opossums, while adults, due to their low-flying hunting style, primarily contend with threats like collisions with vehicles and power lines.

The dwindling availability of nesting habitat resulting from urban and suburban development poses a significant risk to barn owls. With a strong reliance on agricultural structures for nesting sites and fields for hunting, the rapid urbanization of agricultural areas across the state jeopardizes the species.

Black-capped Chickadees (Poecile atricapillus):

NC Range: Western/Appalachian Mountains

Black-capped chickadees, petite resident songbirds, constitute one of the two chickadee species in North Carolina. Their close resemblance to the Carolina chickadee makes distinguishing between the two challenging, yet variations in range distribution and song provide some distinctions.

Black-capped chickadees, petite resident songbirds, constitute one of the two chickadee species in North Carolina. Their close resemblance to the Carolina chickadee makes distinguishing between the two challenging, yet variations in range distribution and song provide some distinctions.

In contrast to Carolina chickadees, known for their elaborate series of notes with diverse pitches, Black-capped chickadees typically sing a concise song consisting of two to three notes, featuring a higher note at the outset.

While Carolina chickadees thrive in the southern regions, Black-capped chickadees predominantly inhabit northern areas, favoring colder climates and higher elevations, particularly in the upper continental United States, Canada, and Alaska. Their population boundary spans from New Jersey to Kansas, with a branch extending down the Appalachian Mountains into Virginia and the mountains of western North Carolina. At this boundary, hybridization with Carolina chickadees is observed.

During spring and summer, Black-capped chickadees primarily feed on caterpillars, transitioning to seeds and berries in winter. Notably, they are known to cache seeds, storing them in specific locations and revisiting them up to 28 days later.

As cavity nesters, Black-capped chickadees either excavate their own tree cavities or repurpose old woodpecker cavities. Nesting and mating occur between April and June, with the female exclusively involved in nest construction, laying a single clutch of six to eight eggs.

Urban development, deforestation, and the loss of dead trees crucial for nesting cavities pose threats to Black-capped chickadees as cavity nesters. Additionally, their preference for northern climates exposes them to risks associated with climate change, pushing their range northward and potentially excluding them from North Carolina altogether as temperatures rise.

Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus):

NC Range: All Regions, but primarily Eastern and Piedmont

The northern bobwhite, also recognized as the Virginia quail or bobwhite quail, is native to Canada, extending as far south as Mexico and Cuba. Belonging to the quail family, it is a medium-sized bird identified by its distinctive “bobwhite” whistle.

The northern bobwhite, also recognized as the Virginia quail or bobwhite quail, is native to Canada, extending as far south as Mexico and Cuba. Belonging to the quail family, it is a medium-sized bird identified by its distinctive “bobwhite” whistle.

As a ground-dwelling species, the northern bobwhite exhibits a preference for agricultural fields, grasslands, and woodlands. With its highly camouflaged and reserved nature, this elusive bird tends to freeze when feeling threatened, seamlessly blending into its environment. While generally solitary, it may form groups, known as coveys, with up to twenty individuals by the end of summer.

In contrast to species favoring mature forests, northern bobwhites thrive in early successional habitats. Historically, before European settlement, they were prevalent in areas managed by Native Americans through controlled burns. Post-European settlement, agricultural landscapes became their primary habitat.

Feeding on grassland and ground-dwelling insects such as ticks, grasshoppers, crickets, and spiders, northern bobwhites also consume seeds, grains, berries, and partridge peas.

Due to their ground-dwelling nature, northern bobwhites face numerous predators, including skunks, raccoons, hogs, mice, armadillos, opossums, foxes, coyotes, bobcats, birds of prey, feral cats and dogs, and fire ants. Nest failure, often a result of predation, is common, with hens nesting multiple times before successfully producing a clutch.

Habitat loss, arising from the development of natural landscapes and agricultural lands, along with habitat fragmentation, invasion by exotic plant and insect species (particularly fire ants), and the absence of prescribed burning, pose significant threats to the northern bobwhite. Controlled burning is crucial for maintaining the early successional woodlands and grasslands essential for their survival.

Piping Plovers (Charadrius melodus):

NC Range: Coastal

The piping plover, a diminutive shorebird indigenous to North American coasts, currently maintains a few populations along the Atlantic coast, extending to Canada, the shores surrounding the Great Lakes, and the Northern Great Plains in the upper Midwest United States. Preferring sandy and gravel beaches, it possesses effective camouflage, making it inconspicuous while stationary.

The piping plover, a diminutive shorebird indigenous to North American coasts, currently maintains a few populations along the Atlantic coast, extending to Canada, the shores surrounding the Great Lakes, and the Northern Great Plains in the upper Midwest United States. Preferring sandy and gravel beaches, it possesses effective camouflage, making it inconspicuous while stationary.

During low tide, piping plovers forage along coastlines for insects, marine worms, and crustaceans.

Breeding activities typically commence in late March, marked by male plovers engaging in courtship flights and displays to attract potential mates. After forming pairs, males create scrape sites on sandy beaches, which the female evaluates before selecting one. Once chosen, the female camouflages the scrape with shells and shoreline material, allowing the male to mate.

Clutching four eggs, piping plovers hatch their offspring around mid-April. While incubating the eggs, parents employ a “broken wing display” to distract and lead potential predators away from the nest.

As small shorebirds, plovers encounter various predators, especially during their vulnerable young stages or while nesting. Raccoons, crows, feral cats and dogs, foxes, and others pose threats. Additionally, their shoreline nests remain in constant peril from high tides and coastal storms.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, piping plovers were targeted for their feathers, sought after for hat plumes. This exploitation contributed to their initial decline, addressed by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918. Nevertheless, their population continued dwindling due to habitat loss, degradation, and the impact of shoreline recreational activities.

Numerous state and federal agencies collaborate to protect piping plover nesting habitats. Despite these efforts, the species confronts a myriad of threats to its survival, encompassing increasing habitat loss, human disturbances, domestic animals, and the adverse effects of climate change, particularly rising sand temperatures and sea levels, which unfortunately undermine progress to protect and restore this species.

Ruffed grouse (Bonasa umbellus)

NC Range: Western

Ruffed grouse stand out as the most widely distributed gamebird, spanning from the mountains of western North Carolina through Canada and Alaska. Remaining non-migratory, they possess effective camouflage tailored to woodland forest floors, especially those abundant in aspen.

Ruffed grouse stand out as the most widely distributed gamebird, spanning from the mountains of western North Carolina through Canada and Alaska. Remaining non-migratory, they possess effective camouflage tailored to woodland forest floors, especially those abundant in aspen.

These omnivorous foragers have a diverse diet, comprising insects, berries, seeds, plant buds, and even small amphibians.

Similar to quail, grouse adeptly conceal themselves on the forest floor, remaining inconspicuous until approached. When disturbed, they erupt into flight with dramatic and noisy wingbeats.

Choosing the forest floor for nesting, ruffed grouse typically opt for logs and stumps as nest sites. Egg-laying occurs around May, resulting in clutches of approximately 9-14 eggs.

As partially ground-dwelling birds, ruffed grouse share common predators with Northern bobwhites, including birds of prey, coyotes, foxes, feral cats and dogs, snakes, and fire ants.

The primary threat to ruffed grouse is habitat loss, encompassing forest clearing for agriculture, tree plantations, and urban development. Despite some parallels with quail, ruffed grouse differ in their requirement for mature deciduous forest habitat. Consequently, clear-cutting for development poses a significant danger to the species. In addition to habitat loss, ruffed grouse also face challenges from West Nile Virus, which emerged in the United States in 1999.

This Giving Tuesday, you can make a difference for North Carolina’s birds. From cardinals to painted buntings, your gift will restore habitats and strengthen conservation efforts—and thanks to NCWF’s Board of Directors, every dollar will be matched 1:1, up to $40,000! Double your impact for the birds that call North Carolina home.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager