NCWF Scholarship Recipient Bailey Kephart Researches Federally Threatened Black Rails

Nestled within the high marshes of North Carolina’s coastline, an entire ecosystem thrives, hidden from plain sight amid the grass and needlerush. Life unfolds discreetly here, contributing to an orchestra of natural sounds. Occasionally, amidst the chorus, a distinct call

Black rail researcher and 2022 NCWF scholarship awardee Bailey Kephart.

emerges—a series of chirps followed by a soft purr.

“This song is known as a ‘kickee-doo,’” explained black rail researcher and 2022 NCWF scholarship awardee Bailey Kephart. “When you hear it for the first time, you’re like, ‘What? That’s a bird?’ Most people wouldn’t notice it.”

Kephart, a graduate student at East Carolina University, is currently working on her thesis examining black rail habitat selection in correlation with prescribed burning and the circadian breeding patterns of black rails, specifically along the North Carolina coast in Pamlico and Carteret counties.

Kephart’s research has implications for black rail species management, particularly around how breeding black rails utilize habitat under specific burn regimes and how to optimize the timing of these burns to align with their breeding cycle.

Her journey into the sensitive study of black rails began during her undergraduate studies at the University of Central Oklahoma, where she served as a technician researching yellow rails in the Red Slough Wildlife Management Area.

“At first, I didn’t have a particular interest in rails,” Kephart said. “But my undergraduate advisor, Dr. Chris Butler, had flyers all around our biology building inviting students to go out and catch birds on the weekend. So I went into his office and expressed interest. We went out the next week, and that was kind of the beginning of it all.”

Following her graduation, Kephart was directed towards Dr. Susan McRae, at East Carolina University, who expressed interest in supervising Kephart’s study of black rails. Soon, she was immersed in the quest to locate this elusive coastal species. However, the endeavor of researching the species is far from easy.

Black Rails in the Balance

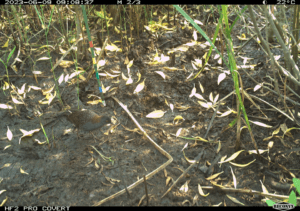

A trail camera photo of an adult black rail from 2022 . The pole in the background is installed to monitor the water levels at the time of a triggered photo capture.

As ground-nesting birds, black rails spend the majority of their time concealed within stands of wild Distichlis and Sporobolus grasses, utilizing natural materials for nesting under umbrella-like formations. Their adept camouflage, coupled with their aversion to flight and swift on-ground movements, render them masters of concealment.

“It’s kind of insane how they stay so hidden and quiet,” Kephart said. “You don’t hear grass rustle when they move or anything. They’re so sneaky, it’s like magic.”

Yet, their mastery of camouflage and evasion is not the sole factor contributing to their elusive nature. Designated as federally threatened since 2020, black rails have witnessed a staggering decline in their habitat, with estimates suggesting a loss of over 90% since the 1900s. Bryan Watts, Director at The Center for Conservation Biology (CCB), approximates a decline of over 70% or greater in the black rail population since the same period.

At Cedar Island Wildlife Refuge, once a stronghold for black rails in the state, freelance surveyor John Fussel reported hearing extensive choruses of black rails in the 1980s, with 10 to 12 calls echoing in a single area. However, according to Kephart, such occurrences have become increasingly rare.

She regularly conducts callback surveys, going out to suspected black rail habitat areas and playing kickee-doo sounds on a speaker, recording and documenting the responses (or “callbacks”) of the birds on the landscape, and at what times she receives them.

Kephart inspecting the trail camera set up used to capture black rail behavior during their breeding season (May-August).

“I’m lucky to hear maybe two calling at once,” remarked Kephart. “I usually don’t hear anything. The population has certainly declined, but most of the declined quantitative numbers are estimations because they’re so secretive and hard to find.”

The primary contributors to black rail declines include habitat degradation, fragmentation, and erosion induced by climate change-induced flooding. Additionally, as ground-nesters, black rail eggs and fledglings are vulnerable to predation, primarily by raccoons and snakes.

Moreover, black rails undergo a period of flightless molt shortly after hatching, rendering them highly susceptible to predators and, in some instances, encroaching fires.

“Black rails depend on emergent habitat comprised of grasses and brush, which likely means that prescribed burning is really important for creating that habitat,” Kephart said. “But ideally, burns should be timed to when they aren’t going through that first molt or incubating eggs. So that ‘sweet spot’ between vulnerable periods is kind of what I’m trying to determine through my research.”

Monitoring Black Rails, and The Road Forward

Due to their elusive nature, discerning black rail mating and breeding behaviors poses a formidable challenge. Notably, black rails engage in biparental care—a rarity among avian species. Both parents contribute to nest maintenance and incubation, with the male often assuming nesting duties alongside the female.

Black rails have been found to have multiple clutches per breeding season, with some individuals laying up to three each year. The typical clutch size for black rails is anywhere from 7 to 13 eggs, a number fairly common among ground-nesting birds. This high number of eggs within a clutch compensates for the egg and hatchling mortality that is common in birds that nest below the protective tree canopy. The survival rate of these clutches can range from 1 to 7 chicks.

This high fecundity rate offers promise for species recovery, contingent upon the preservation of breeding adults and nesting habitats. However, due to their elusive nature, monitoring breeding behaviors remains challenging. Kephart and other black rail researchers avoid seeking out nests to minimize disturbance to their nesting habitat or outright destruction of nests. This caution makes studying nests and clutch mortality difficult to assess.

Kephart and her technician from last year – Hailee Quintero – geared up to trudge through an especially muddy and mosquito-infested marsh area to conduct research.

To detect black rails, researchers employ various techniques, including aforementioned callback surveys, the implementation of Autonomous Recording Units (ARUs) to capture vocalizations, and trail cameras positioned in suspected nesting areas. The funding provided to Kephart as an NCWF scholarship awardee went directly towards transportation to field research areas. She attests to the efficacy of such ARUs in her research – particularly as she currently has over 6,000 hours of recordings cued for analysis. Additionally, the trail camera footage from the field yielded notable findings.

“We put trail cameras out to hopefully get footage of a black rail moving through, maybe even with chicks. It’s really rare, but incredible when it happens. It’s almost like capturing a photo of Bigfoot,” Kephart laughed. “But I did get a photo of an immature black rail, which was the first evidence of an immature black rail in North Carolina in 135 years. We’ve seen adults since then, but not immature birds. So capturing that on camera means that they’re still breeding here.”

Such discoveries, coupled with findings by fellow researchers such as Christy Hand from the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources, offer hope for black rail conservation. Hand, who provided guidance to Kephart in her research, was the first to document the duration of the black rail flightless molt period and captured instances of adults mating while still caring for young chicks, demonstrating the species’ encouragingly high fecundity rate evidenced by their ability to continue breeding before their previous brood reaches maturity. However, uncertainties loom over the species’ future, with projections suggesting potential extinction within 50 years.

“Even as we try our best to nail down these suitable habitat qualities to figure out how we can best manage them, we’re seeing that there’s a lot of decisions we need to make quickly before it’s too late,” Kephart said. “That’s the sort of catch with this species: there is a lot we need to find out, but we don’t have time to forgo management until the knowledge gaps are filled. As long as we can balance research effort with

A rare photo of an adult black rail from the trail cameras last year.

active management decisions, then I think that there is certainly a chance they can make it past that 50-year deadline.”

Despite the daunting task of black rail recovery, Kephart remains optimistic, particularly regarding the role of North Carolinians and private

landowners in aiding conservation efforts.

“Black rails are usually not found in residential areas unless they can really hide themselves in vegetation, far enough away from disturbance. Undisturbed habitat for these birds can be really hard to find,” said Kephart. “But landowners can help with that, especially if they own portions of grassy, high-marsh land on the coastal plain that receives less than five centimeters of water on average. There are local organizations, such as the North Carolina Coastal Land Trust, that can provide landowners with information if they are interested in preserving and/or managing their land for the benefit of these birds or other wildlife.”

Education around the species and its sensitivity are also crucial, to minimize tourism and development impacts on its fragile habitat, and to raise awareness around this remarkable and irreplaceable staple of North Carolina’s marshland ecosystems.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager