“What is an ecosystem, anyway?” : How wildlife fits into ecological communities and drives ecosystem function

“Harmony with land is like harmony with a friend; you cannot cherish his right hand and chop off his left…The land is one organism. Its parts, like our own parts, compete with each other and cooperate with each other. The competitions are as much a part of the inner workings as the cooperations. You can regulate them – cautiously – but not abolish them.” – Aldo Leopold

An ecosystem, as defined by Merriam Webster, is “the complex of a community of organisms and its environment functioning as an ecological unit”, wherein these ecological communities are defined as “a group of organisms, including plants, animals, and microbes, that interact with each other and with their physical environment in a specific area.”

Ecosystems have interconnected parts which are complex in their relationships. Some interactions are simple or direct, such as birds relying on berries and insects for sustenance, while others are more complex, like the impact ocean temperatures have on sea level rise, weather patterns, and plant and animal communities.

But regardless, ecosystem parts are interconnected, with the plant and animal communities and their individual members profoundly impacting one another. While the collection of species within a certain area is referred to as an ecological community, the combination of these communities, the abiotic (or “non-living”) environment and conditions, and the ways in which these entities interact create dyanmic and interwoven ecosystems. Ecosystems and the communities within them vary from place to place within the state, contributing to North Carolina’s varying natural landscapes and the wildlife inhabiting them.

Ecosystems are dynamic and disrupting one element may affect the larger system as a whole. Aldo Leopold likened this to cherishing one part of a friend while neglecting another, stressing the interconnectedness of land as a single organism where competition and cooperation shape its inner workings. However, ecological integrity is increasingly challenged; globally, nearly half of Earth’s land is intensively farmed or otherwise developed by cities, suburbs, and infrastructure (Flores, 24). This transformation is not benign; it leads to an ecologically depleted world, where ecosystems suffer from our disregard for the species within them, and the intricate relationships between those species.

Alfred Russell Wallace – an accomplice of Charles Darwin – wrote that present day Americans live “in a zoologically impoverished world”, lacking fully intact ecosystems. Anthropologist and nature historian Dan Flores echoes this sentiment, even claiming that “none of us born in the last century has gotten to see any form of a biologically complete America.” The understanding that this impoverishment comes largely from the harm done to ecological relationships is an understanding that Aldo Leopold equates to “living alone in a world of wounds.”

But there are ways to salve these wounds and – more importantly – to keep new ones from developing. This is the practice and hope of conservation – to work towards the health and flourishing of these ecological communities and the ecosystems they comprise.

ECOSYSTEM FUNCTION

In order to work towards protecting ecosystems and ecological communities, it is not enough to know what an ecosystem is. We have to know how they function.

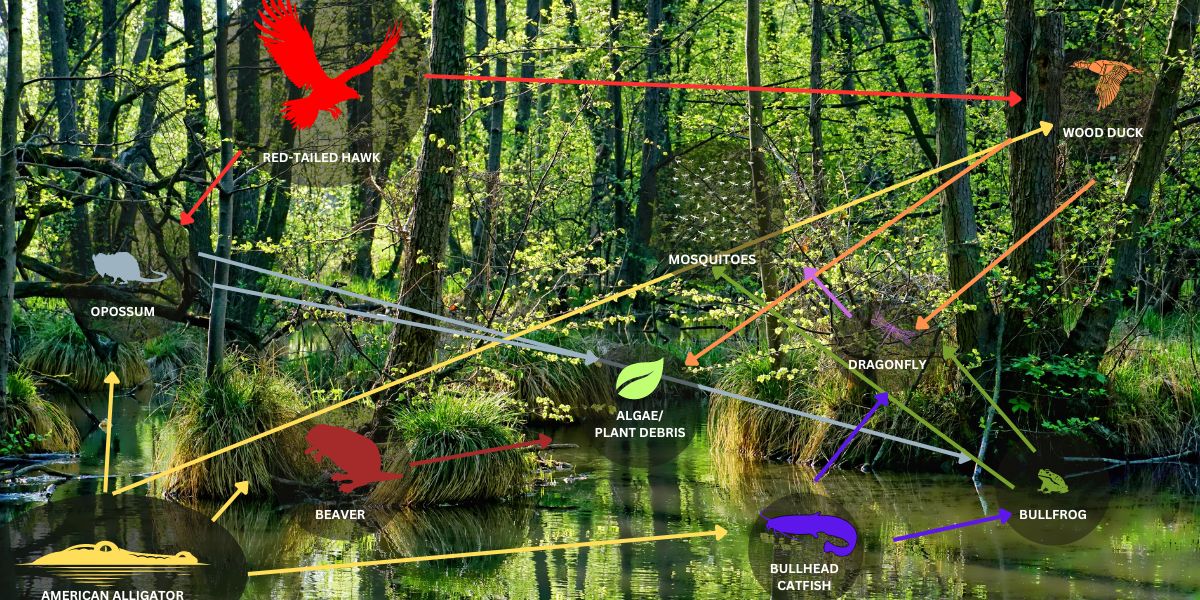

There is no straightforward way to explain ecosystem function, especially since it varies between different ecological communities. Generally, ecosystems operate through the interactions among their abiotic – the land itself and environmental conditions – and their biotic members – plants, wildlife, other organisms, and notably, particularly in the Anthropocene era, humans. In a well-functioning ecosystem, these interactions maintain a balance within the biotic community, a concept explored in ecologist Dan Janzen’s “network analysis”. This theory suggests that the diversity of interactions within an ecosystem predicts its function and overall health better than the mere diverse presence of species. These interactions may manifest in many ways, including:

- Predation: where a predator species keeps prey populations in check, such as hawks controlling squirrel populations.

- Competition for resources: such as several bird species competing for nesting sites in one area.

- Commensalism: where one species benefits from another while the other remains unharmed – like barnacles attached to driftwood or other detritus.

- Parasitism: the opposite of commensalism, where one species benefits from harm done directly to another – like leeches sucking blood from other species.

- Mutualism: where two interacting species benefit from each other – such as bees and flowers both benefiting from the exchange of pollen nectar through pollination.

- Herbivory: species that feed on plant life, controlling plant life and shaping plant communities – such as elk grazing grasslands.

Though many species interactions manifest through food webs, where one species (whether animal or plant) feeds on another, food interchange amongst and between these communities is not the only type of ecosystem function. As an example, south of North Carolina, gopher tortoises dig burrows in the soft sand of longleaf pine ecosystems. These burrows are then used by a variety of other species like rabbits, frogs, snakes, and more.

Another example of ecosystem interaction is the trophic cascade phenomenon, which illustrates how the presence or absence of predators affects an ecosystem. When predator populations increase, prey numbers decrease which in turn reduces predator numbers in subsequent years. This cyclical balance helps regulate populations and supports ecosystem health. Predator-prey interactions also drive natural food chains, transferring energy from sunlight through trophic levels, with plants at the base and large predators at the top. This energy transfer is crucial for sustaining a robust ecosystem.

These ecological processes aren’t confined to large predators alone; similar dynamics occur between insect larvae and songbirds, demonstrating the interconnectedness of species within ecological communities. The removal of a species from its historical ecological niche, whether through extinction or displacement, disrupts not only that species but also its entire native community.

WHAT ARE NORTH CAROLINA ECOSYSTEMS?

North Carolina has many types of ecological communities, which produce subsequently varied ecosystems, perhaps too many to list here. They vary across region (mountains, piedmont, and coastal plain) . These regions can be seen as looking at the landscape through a macro, wide-angle lens, while focusing on individual ecosystems is like looking through a micro or zoom lens. The ecosystems that exist within those larger regions of the state include salt marsh, estuary, pine savanna, cypress swamp, deciduous forest, riparian zone, mountain cove forest, grass bald, wetland, among others.

Specific plant and wildlife species may be found in only one particular community or they may appear in more than one, so it can sometimes be difficult to determine where one community and its resulting ecosystem ends and another begins. In fact, as noted by David Blevins and Michael Schafale in Wild North Carolina, some ecosystems may not be recognizable at all: “Even many forested places that appear unused at first glance do not resemble what nature would put there on its own… This is true of most places that once were plowed and of many forests that were clear-cut in the last few decades. Thus, one of the first questions to ask, and sometimes one of the hardest to answer, is whether a place is a natural community at all.”

But what do these North Carolina ecological communities and their ecosystems actually look like today? Where are they located in the state? And why are they so important for the people, species, and natural spaces within our state? We answer these questions and more in our blog post:

Sources:

“Wild New World: The Epic Story of Animals and People in America” by Dan Flores

“Wild North Carolina: Discovering the Wonder of Our State’s Natural Communities” by David Blevins and Michael Schafale

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources