Endangered North Carolina: Taking a look at some of the state’s endangered species, and how you can help

Endangered Species Day, celebrated each May, is a day to raise awareness for the species we are most at risk of losing. It certainly does not seem like a day to “celebrate” in the traditional sense, particularly when so many North Carolina species – such as Atlantic sturgeon, Carolina northern flying squirrel, red wolf, and bog turtle – are imperiled. This Endangered Species Day, we will hold conviction and celebration in tension. Conviction to do our part in ensuring endangered species recover. And celebration of the species – such as wild turkey, bald eagle, river otter, wood duck, and certain native pollinator species – successfully restored or kept from endangered status through on-the-ground conservation work and critical wildlife policy.

Their recovery reminds us that progress is possible—and worth fighting for.

Unfortunately, a major threat to the Endangered Species Act (ESA) is now unfolding. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service under the new administration have proposed a rule that would dramatically weaken how the ESA protects wildlife. Specifically, the agencies aim to repeal a longstanding regulation—dating back to 1975—that defines “harm” to include the destruction or degradation of essential habitat.

Under the ESA, actions that “take” a listed species are prohibited, and for decades, that has included harming species by damaging the habitat they depend on. The proposed change would narrow the definition of “harm” so drastically that only directly killing an animal would count as a violation—stripping away habitat protections critical for survival and recovery.

NCWF strongly opposes and is working with partners to address this proposed rollback – one which threatens to undermine decades of conservation progress and endanger species already on the brink.

“It is simply absurd to work to accomplish wildlife conservation without focusing on habitat,” said NCWF CEO Tim Gestwicki. “This ill-conceived proposal undermines not only the credibility of those making them, but fully handcuffs any realistic means to keep declining species from becoming endangered or losing valuable wildlife ecosystems.”

Focusing on species of greatest concern and their habitats is critical to reversing wildlife declines. Unfortunately, underfunded wildlife agencies often lack the resources to meet the growing demand for conservation. That’s why North Carolina Wildlife Federation’s focus is on securing dedicated federal funding through Congress. The best and most promising effort to date is the Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (RAWA). Fortunately, North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis and New Mexico Senator Martin Heinrich are working diligently to find a legislative path forward for this important bill.

Spruce-fir moss spider (Microhexura motivaga)

Spruce-fir moss spider (Photo by USFWS Southeast)

The spruce-fir moss spider (Microhexura montivaga) is a state and federally endangered species found in high-elevation spruce-fir forests, primarily in the Appalachian Mountains, including North Carolina.

This small, nocturnal arachnid typically measures around 0.2 inches in body length, making it one of the smaller spiders in its region. It is unique for its specialized habitat requirements, living primarily on the moist, mossy ground (bryophytes) under the cover of spruce and fir trees in cool, shaded areas.

These spiders create webs in the leaf litter and moss found beneath the forest canopy, where they feed on tiny invertebrates such as springtails, mites, and other small arthropods. Their habitat is critical to their survival, as they rely on the cool, humid microclimate provided by the dense evergreen cover of these high-elevation forests.

Due to their specialized habitat requirements, the range of the spruce-fir moss spider has always faced limitations, and populations remain low. The spruce-fir moss spider was discovered in 1923, but it wasn’t until the 1980s that work began to recover the species after facing threats from habitat loss driven by logging, atmospheric pollution and acid rain, and the introduction of the invasive Balsam wooly adelgid.

Since arriving in the 1900s, the balsam woolly adelgid has wiped out about 95% of mature fir trees in high-elevation forests, severely damaging the habitats of spruce-fir moss spiders and other wildlife.

This habitat loss is made worse by acid deposition from rain and fog, which is common in these high-altitude environments. The moisture in the air pulls pollution down from the atmosphere, delivering it to these ecosystems in the form of acid rain. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Southern Appalachians experience some of the highest levels of acid deposition in North America. This further harms forest health and reduces the productivity of red spruce and Fraser fir trees.

As a result of these environmental threats, this species was listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) in 1995. The spruce-fir moss spider is now found only in a few isolated locations on fewer than 25 mountaintops and six high elevation areas in Virginia Balsam Mountains in Virginia, Grandfather Mountain in North Carolina, Roan Mountain in North Carolina and Tennessee, Black Mountains in North Carolina, Plott Balsam Mountains in North Carolina and Great Smoky Mountains in North Carolina and Tennessee (USFWS). Today, with six known populations it is one of the rarest and most critically endangered spiders in North America.

The spruce-fir moss spider has an extremely limited range due to its very specific habitat requirements. As a result, conservation efforts focus on several key strategies: educating land managers on how to identify suitable habitats and encouraging the protection of these areas; safeguarding important sites on private lands in the Plott Balsams and Black Mountains; monitoring the effects of atmospheric pollution and acid rain; studying the biological relationships within these ecosystems; mapping the distribution of spruce-fir habitats across the region; and exploring forest management and reforestation techniques that could support the spider and other dependent species.

The hope is that with sustained protection of its habitat, the spruce-fir moss spider may one day be able to stabilize and even increase in numbers.

Red wolves (Canis rufus)

Red wolves are one of North Carolina’s most popular endangered species among supporters- but also one of the state’s most imperiled species and the world’s most endangered wild canid.

Red wolves have a historic range from southeastern Texas to southern Pennsylvania. Their thick fur coat is generally light brown with red accents, their namesake color. Though they are often confused with other canid species, they are notably larger than coyotes but smaller than the western gray wolf.

As an apex predator in their native range, red wolves are essential for sustaining ecosystem balance through the predation of prey species. The impact that red wolves have on the landscape – and their subsequent removal from the landscape – is known as “trophic cascade”, a subject expanded in the video How Wolves Change Rivers.

Red wolves are federally listed under the ESA of 1973 and are managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). While this level of protection affords red wolves special considerations, it also makes the work of the biologists critically important because species recovery is dependent on the genetic diversity of a limited number of red wolves and the effectiveness of the methods used to increase population numbers. Literally, every red wolf counts.

Red wolf recovery utilizes management techniques such as captive breeding, island propagation, red wolf release, coyote sterilization, and pup-fostering.

Through the Red Wolf Center, NCWF and USFWS offer educational opportunities and community engagement for the Red Wolf Recovery Program. You can visit the center in person and register to attend red wolf webinars through our website.

In collaboration with USFWS’ Partners Program, NCWF rolled out Prey for the Pack, a cost-share program to assist private landowners in making habitat improvements for red wolves and other wildlife on their properties. Any landowners not wanting to apply for the cost-share portion of the program can still support red wolves by becoming a “supporter” and completing a zero-cost agreement.

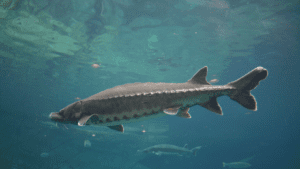

Atlantic Sturgeon (Acipenser oxyrinchus oxyrinchus) – when present in inland waters

Atlantic sturgeon

Atlantic sturgeon are a species of anadromous fish, meaning they spend much of their time in coastal salt water but move along inland freshwater systems to spawn. They are long-distance travelers known to move up to 950 miles in between the ocean and their spawning areas.

Atlantic sturgeon are large fish known to grow up to seven feet in length and to live up to 60 years. They have five rows of protective bony plates called “scutes” and two rows of prenatal shields along their body in addition to a shark-like heterocercal tail, all contributing to their prehistoric appearance. In fact, the species dates all the way back to the dinosaur age and is a member of Acipenseridae, one of the oldest families of fish.

The Atlantic sturgeon population experienced significant declines in the 1900s due to commercial fishing practices, caviar production, and loss of access to their spawning grounds in freshwater systems – largely resulting from dam construction impeding access from coastal waters. Up until the 1800s, the second largest caviar fishery in the US was located in Chesapeake Bay – with lower portions just above the North Carolina-Virginia state line – and utilized unsustainable and largely unregulated harvesting practices. As a result, the Atlantic sturgeon was listed as a federally endangered species in 2012.

The harvest of Atlantic sturgeon is not allowed in North Carolina and any Atlantic sturgeon captured incidental to fishing for other species must be returned to the water alive.

If you encounter a wild sturgeon, please contact the NCWRC’s Division of Inland Fisheries at (919) 707-0220. Include the time, date, and location of the encounter, the approximate length of the fish, and a good-quality photograph (showing the mouth and anal fin for species verification).

Carolina northern flying squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus coloratus)

The Carolina northern flying squirrel is one of two species of flying squirrel in North Carolina. Their cousin species, the southern flying squirrel, sticks to lower elevations while the Carolina northern flying squirrel resides in higher elevations, usually at least 4,000-5,000 feet above sea level. They largely subsist on a diet of lichens, mushrooms, seeds and nuts.

Carolina northern flying squirrel

Their high-elevation population range, combined with their nocturnal behavior, keeps this species hidden and largely unnoticed by human eyes. So hidden, in fact, that the species remained undiscovered until the 1950s. However, it was listed as endangered in 1985, a short 35 years later. Their endangered status came as a result of deforestation and forest fires, which eliminated crucial habitat. The introduction of the invasive balsam and hemlock woolly adelgids further damaged balsam fir and hemlock trees, forcing the squirrels to move to less ideal tree species.

This squirrel species is found in North Carolina, including: Long Hope Mountain, Roan Mountain, Grandfather Mountain, Unaka Mountain, the Black-Craggy Mountains north and east of the French Broad River Basin, and Great Balsam, Plott Balsam, Smoky, and Unicoi Mountains south and west of the French Broad River Basin.

West Indian Manatee (Trichechus manatus)

Often an overlooked North Carolina species, the West Indian manatee, also known as the Florida manatee, is an aquatic that primarily lives in freshwater and brackish marine ecosystems on the coast of the southeast US, where they largely subsist on a diet of underwater grass beds. Related to elephants, they are a very large species and can grow up to 13 feet long and weigh up to 3,500 pounds.

West Indian manatee

They are considered a seasonal occupant of North Carolina, with most sightings occurring in the latter half of the year, between June and October.

The West Indian manatee has suffered significantly from a combination of habitat loss and collisions with boats. Much of their habitat loss is a result of harmful fertilizer, sewage, manure, and development runoff, which cause algae blooms that are harmful and sometimes even fatal to manatees.

As a species that prefers shallow water habitats, the manatee is at great risk of harm from collisions with boats and other watercraft. Though manatee sightings are rare in North Carolina, it is advised to keep an eye out for manatees when boating in their preferred environments, particularly during the summer season on the coast. In the event that you spot a manatee, be prepared to turn off your boat propeller so as not to accidentally injure the animal.

Kemp’s ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

Multiple sea turtle species are widely known and recognized as endangered. However, many don’t know that the Kemp’s ridley is the rarest of all sea turtles, and that more that can be done for their conservation.

Kemp’s ridley sea turtles – like West Indian manatees – are seasonal occupants of the North Carolina coast. Spending much of their time hunting for fish and shellfish, they use North Carolina coastal beaches as nesting grounds and are known to return to where they were born.

Kemp’s ridley sea turtle

The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is smaller than most, with a maximum length of two feet and weighing roughly 100 pounds.

They are also a communal species of sea turtle, sometimes coming ashore to nest in large groups, rather than in isolation like most sea turtles. When in Mexico, they may gather by the thousands to lay their eggs in an event known as the arribada (Spanish for “arrival”).

Sea turtles rely on historic nesting grounds to lay their eggs, meaning they will return to habitats they have frequented in the past. Because there may be years in between a Kemp’s ridley sea turtle’s return to a nesting ground, some turtles find that their once welcoming home has been modified in their absence. Nesting sites may become poached or accidentally destroyed by beach vacationers and coastal development. Coastal litter – including nets and fishing gear – also poses a risk of harming sea turtles, often entangling and drowning them.

As a result of these habitat threats, all six species of sea turtle that nest on the shores of the US are listed under the ESA, but Kemp’s ridley sea turtle is most at risk. Other species of sea turtle can be found throughout the world’s oceans, but the Kemp’s ridley sea turtles only nest on a few special beaches – including those on the coast of North Carolina. Though there has never been a recorded arribada, or mass nesting event, the declining population numbers require the protection of the few turtles who nest in isolation or in small groups on the North Carolina coast.

Cape Hatteras National Seashore is a hotspot for Kemp’s ridley sea turtles and, as such, is heavily monitored from May 1st to September 15th, during their breeding season. Unlike most sea turtle species, Kemp’s ridley sea turtles often nest during the day, meaning researchers can easily take measurements of the turtles and apply special tags to track both individual turtles and record population data.

If you come across a sea turtle of any kind on your coastal excursions, be sure to maintain a safe distance and report the sighting to the correct authorities. Any interaction with sea turtles could damage nesting sites or cause unnecessary stress to nesting mothers.