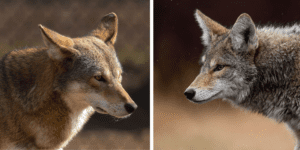

A Scientific Look at Predator-Prey Relationships and Efforts to Reduce Red Wolf and Coyote Hybridization

by Dr. Liz Rutledge, director of wildlife resources, and Katerina Ramos, red wolf education and outreach coordinator

Finding a mate can be challenging with a limited number of red wolves on the landscape. When a red wolf mate isn’t available, red wolves may breed with coyotes, negatively impacting red wolf recovery efforts.

One method biologists use to limit the hybridization of red wolves with coyotes is to sterilize coyotes within the Eastern North Carolina Red Wolf Population. Biologists rely on the understanding of the Placeholder Theory that sterilized coyotes will hold their territories without reproducing, reducing local coyote numbers and their food needs since they will not produce litters of coyote pups.

Male coyotes receive a vasectomy, females undergo tubal ligation, and the sterilized coyotes are released back to their original capture site. This ensures the coyote’s hormones are left intact, motivating them to continue protecting their territories from other coyotes and preventing the birth of hybrid pups. Sterilized coyotes will maintain their territories as placeholders unless red

wolves eventually displace them.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) partners with a local veterinarian in eastern North Carolina for coyote sterilizations. Biologists place white Very High Frequency (VHF) collars on these individuals for identification and monitoring purposes once they’re returned to the wild. Any coyote, including sterilized individuals, can be harvested by hunters or landowners. When left on the landscape, however, sterilized coyotes can benefit landowners wanting to manage coyote numbers or reduce their take of desired game species.

North Carolina Wildlife Federation encourages red wolf protection by providing financial assistance to trappers who unintentionally capture red wolves, ensuring the safe transfer of these individuals to USFWS and back into the wild. USFWS staff captured 20 canids during the 2021-2022 trapping season, including 12 coyotes that were sterilized, collared and released back into the wild through the Red Wolf Recovery Program.

While pup fostering and coyote sterilization successfully increase red wolf numbers in the wild, the hope is that extensive human intervention won’t always be needed to grow and maintain the population.

Predator-Prey Relationships

Understanding how predator and prey species influence each other through their presence and behavior on the landscape is essential for management, conservation efforts, and the overall environment. The Lotka-Volterra model evaluates these relationships by focusing on the cyclic patterns of predator and prey populations over time using pre-defined mathematical equations.

For example, predator species like red wolves can keep prey such as rabbits, deer, raccoons and rodents in check. When predator populations increase, prey populations decrease, decreasing predator numbers in subsequent years due to reduced food availability. When predator numbers drop, prey numbers rebound. This creates a cycle of population fluctuations and ecosystem balance that depends on the success, abundance, and presence of predators and prey, which can reduce disease transmission and help maintain suitable habitat.

Predator and prey interactions influence natural food chains. Energy that begins in the form of sunlight is transferred up the chain through trophic levels, with plants at the bottom and large predators at the top. This transfer of energy is vital for maintaining a healthy ecosystem. The more complex a predator’s role is in the environment, the more impact they have on prey behavior and available resources.

However, indirect effects of having an apex predator on the landscape also occur. The video How Wolves Changed Rivers details the result of reintroducing Yellowstone’s gray wolves to the environment. It explains the introduction of an apex predator, the gray wolf, and the resulting environmental impacts through newly introduced pressures on prey species.

For example, the pressure from gray wolves changed elk foraging habits, allowing vegetation on riverbanks to flourish. The increased vegetation reduced potential erosion and supported other species of wildlife like beaver and other small mammals. This chain reaction is known as a trophic cascade, explaining the indirect effects a species can have on an ecosystem. As the red wolf population grows in eastern North Carolina, we should begin to see positive ecosystem benefits from the presence of this apex predator.

Learn more

Read: The Long Journey to Recovering Red Wolves

Read: Prey for the Pack: Habitat Improvement Program Benefits Private Landowners and Wildlife

Support: Red Wolf Conservation