Wings of Change: Non-native and Invasive Bird Species in North Carolina

Nestled between the Appalachian Mountains and the Atlantic Ocean, North Carolina boasts a myriad of bird species that occupy diverse ecosystem types. While most of these resident birds are native and have been a part of the state’s natural landscape for centuries, the avian tapestry is evolving with the introduction of both invasive and non-native bird species.

In January, 2024, North Carolina Wildlife Federation spotlighted “For the Love of Birds,” directing attention to the vital avian members of our North Carolina ecosystems. The reality of invasive and non-native species poses new – and often harmful – dynamics to native bird populations.

The terms “invasive” and “non-native” carry specific distinctions often used interchangeably, though they have different meanings. Invasive species, often introduced and propelled by humans, have rapidly expanded their territories, reshaping ecosystems and challenging the balance of native wildlife and plant species. On the other hand, non-native species encompass those birds that have arrived in North Carolina through more natural travel routes, and can enrich or harm the natural ecosystem.

Some bird species listed below – European starlings, house sparrows and Eurasian collared doves – are not protected under the jurisdiction of the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, nor are they listed under the Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

In this piece, we will dive into a few birds in both the invasive and non-native bird species categories.

Invasive Bird Species

European starlings (Sturnus vulgaris)

With iridescent plumage and a range of vocalizations, it is no surprise that this species’ introduction to the US originated in theater. In 1890, 100 European starlings were released in New York’s Central Park, with hopes of introducing every bird mentioned by Shakespeare to the US.

These released birds have since expanded their reach to more than 200 million birds covering the entirety of the continental US and Canada.

European starlings are harmful to their non-native range, particularly in their nesting practices. They are cavity-nesting birds, and are known to eject the eggs from the nests of native bird species, such as eastern bluebirds, wood ducks, northern flickers, buffleheads, flycatchers and tree swallows. They are also destructive to agricultural crops, causing millions of dollars in damages to grain and fruit crops each year, according to the US Department of Agriculture.

House finches (Haemorhous mexicanus)

House finches are native to western North America, but were introduced to the eastern US when pet store owners in New York released a

group of the birds to avoid prosecution for illegally selling them.

As insinuated by their name, house finches most commonly stay around man-made structures including urban centers, suburban neighborhoods, and farms.

They often compete with native bird species for nesting habitat, particularly purple finches. They are also significant disease vectors, having collectively struggled with a pandemic of house finch eye disease, first detected in 1994. These birds can pass this and other diseases along to other finch species, including goldfinches.

House sparrow (Passer domesticus)

House sparrows were released in the US in the mid-1800’s in part to alleviate homesickness for European immigrants, and also to address caterpillar and moth species.

However, their contribution to controlling insect species did not compensate for their uncontrollable rate of reproduction, and harmful interactions with native bird species. Since their introduction, house sparrow populations have boomed to over 150 million individuals. Like house finches, house sparrows prefer to inhabit man-made structures.

House sparrows are notoriously aggressive towards other birds and have been known to harass, kill, or injure young and adult birds that are competing for nesting habitat.

Eurasian collared dove (Streptopelia decaocto)

Similar to house finches, Eurasian collared doves were introduced to the US as a result of a crime. In the mid-1970s, a group of Eurasian collared doves were released during the burglary of a pet shop in the Bahamas.

Similar to house finches, Eurasian collared doves were introduced to the US as a result of a crime. In the mid-1970s, a group of Eurasian collared doves were released during the burglary of a pet shop in the Bahamas.

Since the release, their population has grown and spread across nearly the entire continental US. They prefer urban and suburban locations, which has suited them nicely in their progression northward across the continent. As close relatives of the native mourning dove (Zenaida macroura), and sharing similar feeding habits, Eurasian collared doves have had ample opportunity for expansion due to millet supplied by backyard bird feeders and suburban trees used as nesting sites.

Eurasian collared doves are known to carry Trichomonas gallinae, a parasite of the upper digestive tract. As ground foragers and frequenters of suburban bird feeders and urban areas, Eurasian collared doves may pass Trichomonas gallinae to other bird species, particularly native doves.

Non-native Bird Species

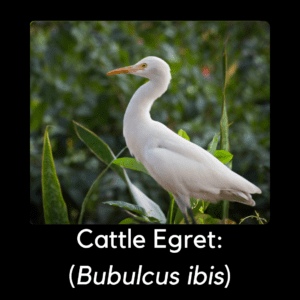

Cattle egret (Bubulcus ibis)

Cattle egrets are thought to have migrated from Africa to South America in the 1930s, either by flight by fair winds or on ships. They quickly adapted to cattle farms and worked their way northward into North America.

Cattle egrets are thought to have migrated from Africa to South America in the 1930s, either by flight by fair winds or on ships. They quickly adapted to cattle farms and worked their way northward into North America.

They were first spotted in North Carolina in Bladen County and on Battery Island in 1956, but have since become a common species in the eastern portion of the state. Unlike other egrets, they tend to stay away from coastal waters and prefer to feed on agricultural land, primarily around livestock.

Though they are a non-native species, their impact on the North Carolina landscape is minimal. They do not pose a threat to other egret or heron species because their feeding habitats and nesting seasons do not overlap.

Brown-headed cowbird (Molothrus ater)

Brown-headed cowbirds have a complicated history, having been displaced by the elimination of American bison. They followed the American bison across the Great Plains, primarily feeding on the insects present on the backs of the bison – a great example of “species symbiosis”, where both wildlife species provide ecosystem services to one another.

Brown-headed cowbirds have a complicated history, having been displaced by the elimination of American bison. They followed the American bison across the Great Plains, primarily feeding on the insects present on the backs of the bison – a great example of “species symbiosis”, where both wildlife species provide ecosystem services to one another.

After the bison was rendered ecologically extinct, brown-headed cowbirds adapted to habitats around cattle farming, leading to their expansion across the majority of the continent.

They are obligate brood parasitic species, indicating a complete loss of nest-building and egg-incubating abilities. Consequently, they expel eggs from the nests of other birds, replacing them with their own eggs and essentially tricking the resident bird into incubating the cowbird’s eggs instead of its own.

As a result of this trait, they are harmful to native birds, – particularly as females lay one egg a day for up to several weeks, disrupting the nests of 220 known bird species, including some endangered species.

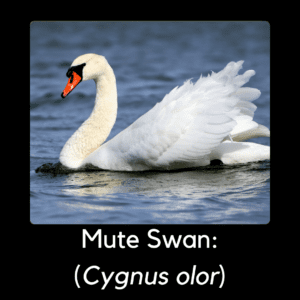

Mute swans (Cygnus olor)

A European species, mute swans were introduced to the US as ornamental features of parks and private estates. These “pet” swans are typically lone individuals, and many states require these swans to be pinioned – a procedure where the joint of the bird’s wing farthest from the body is cut to prevent flight. In North Carolina, it is illegal to introduce mute swans to any public waters.

A European species, mute swans were introduced to the US as ornamental features of parks and private estates. These “pet” swans are typically lone individuals, and many states require these swans to be pinioned – a procedure where the joint of the bird’s wing farthest from the body is cut to prevent flight. In North Carolina, it is illegal to introduce mute swans to any public waters.

While some mute swans may be spotted year-round in small numbers across the state in ponds and lakes, larger breeding populations are located farther northwards, where they are more common and have established themselves as a harmful invasive species – particularly in competing with native waterfowl species for feeding grounds.

Mute swans are often confused with tundra swans. To tell them apart, pay attention to their bill: mute swan bills are orange and tundra swan bills are black.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF Director of Wildlife Resources