High Hopes: North Carolina Treefrogs

As the season shifts towards warmer weather and longer days, many wildlife species emerge from hibernation and begin the search for food and mates. This emergence looks different across species, but for some it brings about heightened mobility, changes in seasonal behavior, and, for certain species, persistent vocalizations.

As the season shifts towards warmer weather and longer days, many wildlife species emerge from hibernation and begin the search for food and mates. This emergence looks different across species, but for some it brings about heightened mobility, changes in seasonal behavior, and, for certain species, persistent vocalizations.

Few experiences rival the symphony of frog calls that accompany the arrival of spring in North Carolina. Highly adaptable animals, different species of frogs are prevalent in most bodies of water – from lake edges to backyard water fixtures to agricultural ponds.

However, these amphibious voices do not solely emanate from the frogs at ground level; they also resonate from above.

In March 2024, NCWF highlighted Wildlife in the Overstory. While there is a multitude of wildlife species observable at ground level, many rely on the shelter and resources provided by trees, particularly those thriving in their canopies. These tree canopies can create an entirely distinct habitat for wildlife, many of which have evolved and adapted to depend upon them. However, these habitats – and the wildlife within them – face increasing threats from deforestation and habitat fragmentation, much of which results from human development and changes in land use.

In this blog post, we dive into some of the amphibian species that rely on these treetop habitats, a reliance evident even in their names: the treefrogs.

Treefrogs in North Carolina

Gray treefrog

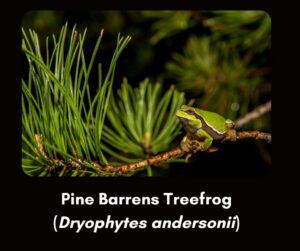

North Carolina tree frog species include the gray treefrog (Dryophytes versicolor), American green treefrog (Dryophytes cinereus), pine woods tree frog (Dryophytes femoralis), barking treefrog (Dryophytes gratiosus), squirrel treefrog (Dryophytes squirellus), and pine barrens treefrog (Dryophytes andersonii). Though there are other species of frog in North Carolina that can resemble treefrogs and are known to climb short vegetation (such as some cricket frogs and chorus frogs), the treefrogs within the genus Dryophytes are better suited to climbing high vegetation, including trees.

Both the pine barrens treefrog (Dryophytes andersonii) and the northern gray treefrog (Hyla versicolor) are featured on the state’s list of Species of Greatest Conservation Need.

From Tadpoles to Treefrogs

Treefrogs derive their name from their ability to scale vegetation, namely trees. However, their lives do not begin in the treetop, but in bodies of water.

Female tree frogs deposit egg clusters near the water’s surface, affixing them to stationary plants like underwater branches or grasses.

Tree frogs hatch from egg clusters as tadpoles and then develop into frogs.

Securely anchored to this vegetation, the eggs nurture tadpoles, which emerge after approximately two to three weeks. This larval tadpole stage lasts around two months, during which time the tadpoles voraciously consume algae and plant matter to fuel their growth into frogs.

However, this growth phase poses risks, as increased movement exposes them to predators such as fish, birds, insect nymphs, and snakes. To avoid these predators, tadpoles often hide and feed in dense aquatic vegetation.

Upon hatching, tadpoles begin to undergo metamorphosis, developing facial features and respiratory structures before growing teeth (better suited for their carnivorous, insect-eating lifestyle on land) and legs. Their tail, initially used for propulsion, gradually shrinks as they transition into their adult form. Once the tail is fully absorbed into the body, young tree frogs venture onto dry land, where they complete their development to the adult stage while feeding on small invertebrates on the forest floor. Upon maturity, they ascend trees, with some treefrog species occasionally descending to hunt in the lower vegetation. Unlike many frog species that remain in or near water, treefrogs generally only return to the water for egg laying.

Nocturnal by nature, tree frogs are able to see colors even in the dark, which helps them maneuver around the tree canopy and detect treetop prey like snails, worms, and insects. Each species has a distinct call, used for marking territory and attracting mates. During mating season, male treefrogs fiercely defend their territory, engaging in wrestling matches with other male treefrogs. After mating, females return to the water to lay eggs.

How Do Treefrogs Climb?

Treefrogs possess specialized toe pads adapted for climbing trees and sticking to leaf surfaces. When examined under a microscope, each toe reveals a treaded pad resembling a car tire, composed of tightly packed clusters of column-like structures. These flexible clusters of columns, along with a thin layer of mucus secreted between them, enable the toes to grip smooth surfaces like leaves and cling to rough edges such as tree bark. Their foot bone structure, featuring claw-shaped segments at the toe ends, also aids in climbing.

Treefrogs possess specialized toe pads adapted for climbing trees and sticking to leaf surfaces. When examined under a microscope, each toe reveals a treaded pad resembling a car tire, composed of tightly packed clusters of column-like structures. These flexible clusters of columns, along with a thin layer of mucus secreted between them, enable the toes to grip smooth surfaces like leaves and cling to rough edges such as tree bark. Their foot bone structure, featuring claw-shaped segments at the toe ends, also aids in climbing.

Climbing trees offers treefrogs numerous advantages. They gain access to a diversity of insects in the canopy, avoiding competition with ground-dwelling frog species and reducing vulnerability to terrestrial predators. However, residing in treetops carries some risks. When lacking foliage cover, treefrogs are often exposed to potential threats like birds and snakes, whereas terrestrial frogs might hide under leaf litter, fallen branches, or rocks, which typically provide concealment from ground predators. But treefrogs’ adaptive camouflage helps mitigate these dangers. For instance, the American green treefrog boasts a lime-green hue with scattered yellow dots, blending seamlessly with verdant foliage of the same color. Similarly, pine woods treefrogs are streaked with various shades of brown and gray, allowing them to blend into pine bark.

Threats Faced

Tree frogs and other amphibians face a spectrum of environmental challenges due to their reliance on both terrestrial and aquatic environments. Chemical pollution, stemming from agricultural and industrial activities, poses a significant threat through the contamination of water sources. With their permeable skin, amphibians are highly susceptible to these toxins, which can penetrate deeper into organ tissue.

Among others, the pine barrens tree frogs, classified as a Species of Greatest Conservation Need, confront various risks primarily due to the spread of non-native species and exotic fish. These invaders compete for food resources and prey on juvenile pine barrens tree frogs, diminishing their populations in water bodies on or near developed and agricultural areas where non-native species thrive.

Deforestation poses numerous threats to tree frogs, depriving them of essential treetop habitat for foraging and refuge from predators. Additionally, deforestation diminishes the availability of vernal pools, crucial components of woodland ecosystems that facilitate amphibian mating and juvenile development. Natural wetlands and vernal pools are particularly devoid of predators due to their temporal nature and serve as vital reproductive sanctuaries for amphibious species. Climate change exacerbates these challenges, prolonging drought periods that either shorten the existence of vernal pools or prevent their formation altogether.

Want to learn more about Wildlife in the Overstory?

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources