Passing By: Remembering Extinct Wildlife in North Carolina

According to LandScope America and the NC Wildlife Resources Commission, there are at least 990 vertebrate species (excluding marine fishes), more than 3,500 invertebrates, and over 5,500 species of plants and mosses.

North Carolina boasts the world’s highest diversity of salamanders, with nearly four dozen species in the Southern Appalachians alone.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park, famous for its elk population, draws visitors worldwide.

North Carolina is the northernmost habitat for American alligators and the southernmost for species like Wehrle’s salamander.

Wild Red Wolves, unique to North Carolina, roam the Albemarle Peninsula. Known as the “Yellowstone of the East,” this area is a migration hub for snow geese and tundra swans.

North Carolina’s estuarine ecosystem is the second-largest in the US and harbors diverse marine life and ancient bald cypress forests on the Black River, which house some of the world’s oldest trees.

These species and their ecosystems scratch the surface of the vibrant array of wildlife North Carolina contains. These species have established themselves over millions of years, shaped by species evolution and ecosystem changes brought about by a variety of factors.

But, despite our state’s rich biodiversity and the species that call it home… there is something missing. In fact, there are several species that are now completely absent on the North Carolina landscape, species that – despite having been a part of this state’s natural heritage for centuries – have disappeared over the course of the last two centuries.

How can species disappear so quickly after being here for thousands and – in some cases – millions of years? What is the common denominator between their disappearances?

The answer is as convicting as it is evidential. The answer is – in large part – us.

And, unfortunately, these extinct North Carolina species may be joined by many others.

Moving Forward

The species described below are examples of what might occur to any wildlife species faced with threats to their habitat, reproductive success, from excessive predation, and access to resources.

Though these species are some of the few to go fully extinct since the time of European settlement, they are not alone in facing threats of extinction, and they are certainly not the only ones to experience significant population declines at the hands of market hunting, habitat loss, and resource scarcity.

Despite their current prevalence, wild turkeys were nearly extirpated from North Carolina in the mid 1950s.

Bald eagles were listed as an endangered species in 1978 throughout most of the United States, when population numbers plummeted as a result of the harmful pesticide DDT.

Elk were extirpated from North Carolina and across the southeastern US as a whole, with the last known wild eastern elk killed in 1877.

Even white-tailed deer, now abundant everywhere in the state – were threatened by extirpation in North Carolina.

Red Wolves still face the difficulties of species recovery in our state as the most endangered wild canid in the world.

The continued presence of these species in North Carolina is due to intensive and tireless conservation and species management, involving close population evaluation by state and federal wildlife agencies.

However, there are wildlife species that still face uncertain futures on a landscape that continues to be developed and – in some places – made increasingly unconducive to their survival.

As those who share a state with these species, we face a decision: will we create a future for these species that will celebrate them as conservation successes, as wildlife saved from the brink of extinction?

Or will we play a hand in adding them to the ranks of species we will never see again as we know them, species that we played a hand in eliminating?

Join us in exploring some of the extinct wildlife species that are no longer present in our state and why we should work to ensure our state’s other species continue to have a place here with us.

Want to help? Stay in the know on NC wildlife updates by signing up to receive NCWF wildlife updates and action alerts and consider donating towards NCWF’s Endangered Species Day campaign to raise $10,000 by May 31st for wildlife in North Carolina.

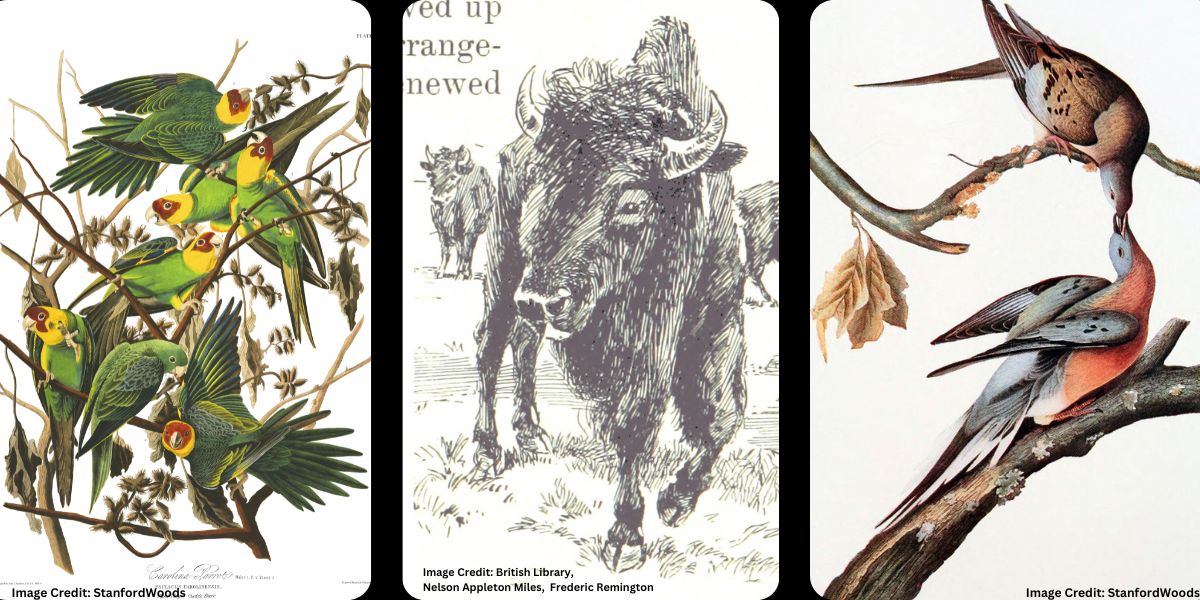

NC Extinct Wildlife – Carolina Parakeet

Carolina parakeets were once present in much of the eastern United States, from New York to Florida and as far west as Colorado.

Carolina parakeets were once present in much of the eastern United States, from New York to Florida and as far west as Colorado.

Carolina parakeets were exceedingly colorful, with tropical color combinations ranging from tangerine orange to turquoise blues, yellows, and greens.

They were the only parrot species native to the eastern United States, and nested in colonies, seeking out cypress swamps as their primary nesting habitat. As cavity nesters, they utilized lightning strike cavities and vacated woodpecker holes for shelter and the rearing of young.

Unfortunately, their cavity nesting adaptation ultimately led to their demise at the hands of cypress swamp logging and agriculture – particularly in the form of introduced European honeybees that competed with the birds for tree cavities.

Though they were declared extinct in 1939, the species had declined to drastically reduced numbers long before then. Evidence suggests that the species had been declining since the Last Glacial Maximum (or the most recent period when ice was at its widest range, covering 25% of the planet’s land area) about 20,000 years ago.

However, the finding that Carolina parakeets seemed to go extinct without evidence of inbreeding insinuates that their final rate of decline was too rapid for the species to adapt to these new anthropogenic environmental threats.

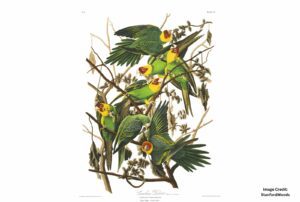

NC Extinct Wildlife – Bison

Some 400,000 years ago, bison ancestors crossed the land bridge between Asia and North America during the Pliocene Epoch. Once here and over time, their numbers reached 40 to 60 million based on estimates in the 1500s. It is unknown how many bison resided in North Carolina, but the early explorers, hunters and naturalists described “plenty of buffalos,” “tracks everywhere,” and robust herds in the western half of North Carolina possibly through the eastern Piedmont physiographic region.

Some 400,000 years ago, bison ancestors crossed the land bridge between Asia and North America during the Pliocene Epoch. Once here and over time, their numbers reached 40 to 60 million based on estimates in the 1500s. It is unknown how many bison resided in North Carolina, but the early explorers, hunters and naturalists described “plenty of buffalos,” “tracks everywhere,” and robust herds in the western half of North Carolina possibly through the eastern Piedmont physiographic region.

There are at least 40 locations in North Carolina named for the “buffalo” including Dutch Buffalo Creek, Irish Buffalo Creek, Buffalo Ford, Buffalo Shoals, Buffalo Cove and the “lost town” of Buffalo. But the bison disappeared from North Carolina 100 years before they were almost wiped out in the western United States at the hand of increased eastern development that eliminated crucial bison habitat and market hunting that decimated herds. Joseph Rice, an early settler of Swannanoa Valley, is purported to have shot the last bison in 1799 near Bull Creek.

There now is a historical marker on the Blue Ridge Parkway, at elevation 3,483 (milepost 373), designating the approximate location. A re-establishment of the “big shaggy” in Buncombe County was attempted in 1919 with “six head of buffalo” but after five years the wild introduction turned to disappointment. Now the bison can only be viewed at places such as the North Carolina Zoo in Asheboro and several bison farms scattered throughout the state.

Read more about bison in North Carolina in our blog post, NCWF and the Carolina Bison Connection.

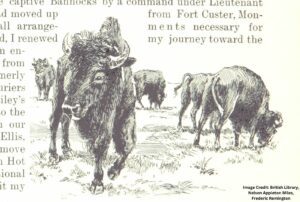

NC Extinct Wildlife – Passenger pigeon

As a migratory bird, the passenger pigeon got its name from the French word, “passeger”, which means “passing by”. Though not closely related, the passenger pigeon resembled the now prevalent mourning dove, with patterns of gray, white and iridescent plumage.

As a migratory bird, the passenger pigeon got its name from the French word, “passeger”, which means “passing by”. Though not closely related, the passenger pigeon resembled the now prevalent mourning dove, with patterns of gray, white and iridescent plumage.

At one time, the passenger pigeon was the single most prevalent bird species on the planet. Though estimates vary, passenger pigeon populations in the United States were likely between 3 and 5 billion during the time of European settlement. According to historian and Wild New World author Dan Flores in relation to the passenger pigeon population size, “A billion is a thousand millions and at those numbers, passenger pigeons made up between twenty-five percent and forty percent of all American birds. Today, house sparrows, European starlings, ring-billed gulls, and barn swallows are the only birds whose global populations top a single billion.”

Even at their largest population density, they were mostly confined to forested areas, which likely came as a result of Native American set fires – a precursor to the controlled burning management strategies employed today. Within wooded areas, passenger pigeons were said to roost so densely that they could topple full-grown trees.

The layers of droppings that these flocks left on the ground could be a foot in depth, smothering understory plant life. But this understory smothering helped to build Eastern forests into what they are today by suppressing the growth of thick undergrowth and fertilizing remaining plant life with nitrogen-rich pigeon droppings.

Their primary diet of hardwood mast helped to ensure their ecosystem impact was scattered across the landscape. Since hardwood mast cycles are somewhat unpredictable and do not occur everywhere simultaneously each year, passenger pigeons had to move from forest to forest in search of food and subsequently did not overwhelm individual forest communities.

However, despite their numbers, European settlement and market hunting were the species’ ultimate downfall. Passenger pigeons were a prized food commodity in city centers and were exceedingly easy to harvest. Large overhead flocks of passenger pigeons were easy targets for shotguns, and there were even recorded instances of people shooting fireworks into passing flocks.

A popular activity in New England states in particular involved releasing captured passenger pigeons as living targets for shotgun shooting. As passenger pigeon numbers began to decline, the pigeons were replaced with clay discs, giving rise to the activity of clay shooting, where these discs are even still referred to as “clay pigeons”.

By the second half of the 1800s, population numbers were experiencing a noticeable decline. However, efforts to preserve the species did not begin until it was too late. By the late 1800s, flocks of mere dozens remained where billions had existed just over 100 years before. Soon after, these last remnants of the global population disappeared.

The species was declared extinct in 1914 following the death of the last known passenger pigeon at the age of 29.

Bachman’s warbler

The most recent species declared to be extinct in North Carolina was the Bachman’s warbler. A migratory bird, it overwintered in Cuba and had a summer breeding range in the southeastern United States.

The Bachman’s warbler had bright plumage and was known to nest and breed in bottomland swamp habitats. It preferred areas on the edge of forested swamps, in dense stands of cane, where they built their nests.

The largest contributing factor to the species’ decline and ultimate extinction was the loss of these bottomland and cane-dense habitats, both in its United States breeding range and its wintering range of Cuba.

The species became critically endangered in the early to mid 1900s, with isolated sightings occurring up until 1988, when the last confirmed sighting occurred in Louisiana. In 2023, the US Fish and Wildlife Service declared the species extinct.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources