The North Carolina Piedmont and its Wildlife

What is the Piedmont?

The Piedmont region of North Carolina lies centrally between the mountainous western part of the state and the Coastal Plain to the east. This area, once part of the Appalachian mountain range, features a varied elevation—from about 1,500 feet above sea level in the west to around 300 feet in the east.

The transition from the Piedmont to the Coastal Plain is not always obvious as you travel across the state. This transition is marked by the Fall Line, where hard rocks of the Piedmont are buried beneath the softer sediments of the Coastal Plain. Although the Coastal Plain is generally lower, in the Fall Line its sediments sit atop the hills while Piedmont rocks are exposed along the rivers (Blevins and Schafale). Where the gradient transitions from the descending Piedmont to the flat Coastal Plain, rivers and streams cascade over the harder rocks of the Piedmont before mellowing out and slowing down as they meander across the Coastal Plain.

Geologically, North Carolina displays a gradient of aging, weathering, and erosion, with the Piedmont positioned between the older mountainous terrain and the younger coastal areas. Consequently, the Piedmont is often described as an “erosional terrain”, with erosion having shaped the Piedmont over time into a gently rolling landscape, dotted with remnant hills.

Charlotte, NC is one of the most highly populated cities in North Carolina, yet shares the Piedmont region with natural settings such as old field habitats.

Piedmont soils are moderately deep, well-drained, and slow to permeate, formed from weathered clayey and silty shale of the Permian age (USDA). These soil characteristics and the region’s warm, moist climate support the Piedmont’s deciduous temperate forests, where seasonal temperature variations bring cold winters and hot, wet summers (NASA). In his book “Temperate Forests”, Michael Allaby simply defines these forest types as follows, “Temperate forests are those found in regions where the climate is temperate.” In the Piedmont, these forests are primarily comprised of oak and hickory trees – with other species like poplar, sweetgum, and maple interspersed. If able to retain native plant composition, the diversity of plant species is greater along these forest edges, creating valuable habitat and forage for wildlife. However, edges and disturbed areas can be highly influenced by the encroachment of invasive plant species.

The relative flatness of the Piedmont has made it amenable to development and agriculture in many areas, which involves land disturbance from bulldozing and plowing, transforming much of the region into cities, suburbs, fields, and some successional pine forests. Yet, oak forests still cover many broad upland flats and ridges, interspersed within developed and pine-dominated areas (Blevins and Schafale).

The Piedmont also encompasses a range of habitat types, including dry coniferous woodlands, floodplain forests, lakes and reservoirs, mesic forests, riverine aquatic communities, and small wetlands (NCWRC). The variability of ecotypes within the Piedmont allows for a diversity of wildlife in the region.

The Piedmont has the highest population density in the state, with over two million people living in Greensboro, Charlotte, Raleigh, and Durham. This population density has led to extensive infrastructure development, expanding into both natural and agricultural areas on the outskirts of these urban centers, often displacing wildlife and fragmenting habitat ranges.

Wildlife in the Piedmont

As a temperate zone situated between the mountains and the coast, the Piedmont holds a vast diversity of wildlife species, with occasional visitors from animals with ranges that may overlap with the coast and the mountain regions.

While the variety of wildlife in the Piedmont is extensive, we’ll focus on three species found in the region, exploring their presence on the landscape, challenges they face, and NCWF’s efforts to assist with these challenges.

Oldfield Deermice (Peromyscus polionotus)

The oldfield deermouse is the smallest member of the genus Peromyscus and is featured on the North Carolina Species of Greatest Conservation Need list. Native to the southeastern United States, they are fairly rare in North Carolina, but do appear in the southwestern Piedmont.

An example of old field habitat, where the old-field deermouse calls home.

As their name suggests, oldfield deermice depend on early successional habitat typical of old field ecotypes, which are “dense fields filled with a variety of flora- typically dominated by the early summer legumes trefoil and trillium, followed by the late season goldenrods and asters” (University of Maryland). In the North Carolina Piedmont, their fur coloration tends to be dark brown to cinnamon while in coastal areas of other states, their fur is much lighter. The variation between colors allows them to blend into the soil and leaf litter of oldfield habitats.

Oldfield deermice rely on areas with sandy or poorly drained soils that are conducive to digging burrows. These burrows reach between one and three feet underground and have two entrances. Inside their burrows, deermice make nests of grass and leaf matter. They are a monogamous species and raise young in pairs within their burrows (Alabama Department of Conservation).

The limited range and population decline of oldfield deermice in North Carolina is likely due to habitat loss resulting from large-scale development, the introduction of invasive species, and the lack of land management practices needed to maintain these old field ecotypes. One such management practice is controlled burning, which can improve forage, seed production, and cover, while protecting the area from wildfire (University of Tennessee, USFWS).

Habitat Restoration in the Piedmont

NCWF has several Community Wildlife Chapters near to locations where oldfield deermice have been observed in the state – notably Mecklenburg, Rutherford, and Cleveland counties. NCWF’s Charlotte Wildlife Stewards, Lake Norman Wildlife Conservationists, Concord Wildlife Alliance, Habitat Builders, and Union County Wildlife Chapters are all active in these areas. The NCWF chapters host habitat restoration projects that benefit a variety of ecotypes, including oldfields and early successional habitat that oldfield deermice and other species depend on.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- Oldfield habitats and other early successional lands are important for wildlife, from bobwhite quail to white-tailed deer to oldfield deermice. Learn more about this important habitat type using the links below:

Forest Dynamics – On Wildlife and Ecological Succession

A Deep Dive into 5+ NC Ecological Communities and the Wildlife Within Them

How Wildlife Fits into Ecological Communities/Drives Ecosystem Functions

Act:

- Participate in healthy land management practices that bolster ecological communities of all types, benefiting wildlife dependent on various successional stages – from early to late succession stages.

- Participate in habitat projects such as invasive species removals that allow for the reestablishment of native plant communities better suited for native wildlife.

Brown-headed Nuthatches (Sitta pusilla)

“Brown-headed nuthatch, February 4, 2019–Warren Bielenberg” by Great Smoky Mountains National Park is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0.

The brown-headed nuthatch is a songbird featured on North Carolina’s Species of Greatest Conservation Need list. Native to the southeastern United States and prevalent in the Piedmont and Coastal Plain of North Carolina, with the greatest numbers in the Piedmont.

Brown-headed nuthatches are a cavity nesting species, and reside in coniferous and mixed woods habitats where they can find an abundance of seeds (particularly pine seeds) and insects. According to the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, the brown-headed nuthatch is the only North American bird to regularly use tools, small twigs and pine needles, to excavate insects from the soil and use flakes of pine bark as makeshift “crowbars” to extract insects from beneath bark layers. Some may even use layers of bark as a sort of “pantry door” to cover their seed caches (The Audubon Society).

As cavity nesting species, they have adapted well to climbing tree trunks themselves, even upside down. As a species dependent on trees and tree cavities, they rely on mid to late successional forest types for habitat and have thus seen significant population decreases as a result of habitat loss.

More often in the Piedmont where their population numbers are greatest, they are commonly seen at backyard bird feeders and birdhouses. Supporting this species in the Piedmont and beyond is important for its recovery and longevity as a continued resident of North Carolina.

NCWF’s South Wake Conservationists Chapter and Brown-headed Nuthatches

Having lost much of its critical nesting habitat, brown-headed nuthatches are in need of nesting space now more than ever. NCWF Community Wildlife Chapters are centered around providing nesting boxes for various species of birds throughout the state, including purple martins, ospreys, barn owls, wood ducks, bluebirds… and brown-headed nuthatches.

This past June, NCWF’s South Wake Conservationists Chapter installed new houses for brown-headed nuthatches at the Glenaire Retirement Community in Cary. These boxes will provide prime nesting locations for brown-headed nuthatches while providing viewing and educational opportunities for local residents.

NCWF’s Old Growth Forest Work

Since 1945, NCWF has been committed to the protection, conservation, and restoration of wildlife and wildlife habitat in North Carolina – and one of those crucial habitat types is old growth forest, an ecotype that is vitally important for brown-headed nuthatches and many other wildlife species.

In August, NCWF’s VP of Conservation Policy Manley Fuller published an Op-Ed highlighting NCWF’s support of the US Forest Service’s National Old Growth Amendment, focused on the protection and management of mature and old growth forests for people and wildlife.

Brown-headed nuthatches require large trees for the construction of nesting cavities; therefore, these trees must be of an age to reach diameters in growth needed to sustain the cavities. These mature forest ecotypes provide brown-headed nuthatches with the nesting sites they need for reproduction and protection from predators.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- Mature, late successional, and old growth forest types are important for numerous wildlife species, including brown-headed nuthatches. Learn more about these habitats and their wildlife at the following links:

Ecological Forestry: Ecological, Social, and Economic Values of Our Forests

The North Carolina Bird Atlas – A Community Science Project Webinar

Act:

- When possible, avoid removing large trees or dead trees also known as snags, from the landscape unless they pose a safety risk, as these trees provide habitat for cavity nesting birds. Also, you can create wildlife habitat in your yard by providing food, water, shelter, cover, and places for wildlife to raise young.

Monarch Butterflies (Danaus plexippus)

Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

Similar to other native pollinators in the state, monarch butterflies are present at various times during their migration. Preferring open spaces, early successional and old field habitats with frequent blooms, as well as edge habitats, the Piedmont has the potential to provide ideal foraging habitat for migrating monarchs.

Monarchs migrate from spring to fall, typically producing four to five generations, with the final generation undertaking the long journey back to their wintering grounds in Mexico.

Monarchs and other pollinators have experienced significant population declines in recent decades due to habitat loss, pesticide use, and other environmental changes. In the Piedmont, rapid development and invasive plant species further exacerbate these challenges. For monarchs and other pollinators to thrive, it is important to introduce a variety of native plants to restore the habitat needed to fulfill their biological processes. Monarch butterflies, in particular, depend on milkweed (Asclepias spp.) for food and reproduction, highlighting the need for plant diversity to support different pollinator species.

NOTE: Not all milkweed is the same!

There are many non-native types of milkweed that are not beneficial to implement in your NC pollinator garden. There are about 16 species of milkweed that are native to North Carolina. The most well-known and easy-to-find species consist of common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), butterfly weed (Asclepias tuberosa), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), and whorled milkweed (Asclepias verticillata). Read more.

A diverse array of native plants, particularly plants that bloom at different times, enhances reproductive opportunities for various species and provides ample foraging resources. Pollinators benefit from a range of pollen and nectar sources, which improves their nutrition and boosts their resilience to diseases and parasites. Protecting ecosystems with rich plant diversity is essential for effective pollinator conservation.

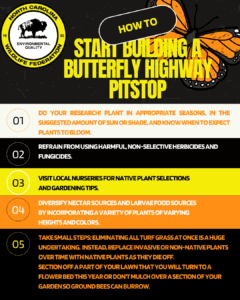

NCWF’s Butterfly Highway

NCWF’s Butterfly Highway focuses specifically on conserving pollinator species, including butterflies, bees, and other beneficial insects. The patchwork of habitat established by Butterfly Highway is especially important for migratory pollinators like the monarch butterfly, which depend on places to rest and forage along their migratory route. Butterfly Highway participants can establish Pollinator Pitstops full of native flowering plants that serve as vital nectar and host plants for butterflies throughout their life cycles. By engaging schools, neighborhoods, businesses, and municipalities in planting and maintaining pollinator-friendly gardens, the program not only supports butterflies but also enhances urban landscapes with vibrant colors and increased biodiversity. Currently, there are more than 3,000 Pitstops registered under the Butterfly Highway program, and the number is growing. Learn how to register your yard as a ollinator pitstop.

NCWF’s Butterfly Highway focuses specifically on conserving pollinator species, including butterflies, bees, and other beneficial insects. The patchwork of habitat established by Butterfly Highway is especially important for migratory pollinators like the monarch butterfly, which depend on places to rest and forage along their migratory route. Butterfly Highway participants can establish Pollinator Pitstops full of native flowering plants that serve as vital nectar and host plants for butterflies throughout their life cycles. By engaging schools, neighborhoods, businesses, and municipalities in planting and maintaining pollinator-friendly gardens, the program not only supports butterflies but also enhances urban landscapes with vibrant colors and increased biodiversity. Currently, there are more than 3,000 Pitstops registered under the Butterfly Highway program, and the number is growing. Learn how to register your yard as a ollinator pitstop.

National Wildlife Federation’s Certified Wildlife Habitat Program

This program certifies properties—ranging from small backyards to large corporate campuses—that provide essential elements for wildlife survival, including food, water, cover, and places to raise young. Participants commit to sustainable gardening practices such as planting native plants, reducing pesticide use, and installing bird feeders and water sources. By transforming yards and public spaces into Certified Wildlife Habitats, this program enhances urban and suburban ecosystems, creating interconnected habitats that support a variety of wildlife species, including monarch butterflies. Learn how to register your yard as a Certified Wildlife Habitat.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- Monarch butterflies are prevalent throughout the state. Regardless of where you live you can help them in their migratory journey. Find out more here:

Wildlife Species Spotlight: Monarch

Monarchs & Pollinators – North Carolina Wildlife Federation

Act:

- Install native flowering plants in your yard or garden to provide nectar sources for migrating monarchs. While you’re at it, register your yard as a Pollinator Pitstop on the Butterfly Highway.

- Avoid using pesticides and herbicides when possible which can harm or kill pollinators and other wildlife.

- Participate in a pollinator planting or invasive species removal with a NCWF Community Wildlife Chapter.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources

Sources:

- Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. (n.d.). Oldfield deermouse. Outdoor Alabama. https://www.outdooralabama.com/rodents/oldfield-deermouse

- Allaby, M. (1999). Temperate Forests. Chelsea House Publications.

- Blevins, D., & Schafale, M. P. (2011). Wild North Carolina: Discovering the wonders of our state’s natural communities. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Georgia Department of Natural Resources. (n.d.). Out my backdoor: Nuthatches at work.

https://georgiawildlife.com/out-my-backdoor-nuthatches-work - NASA. (n.d.). Temperate biome. Earth Observatory.

https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/biome/biotemperate.php - National Audubon Society. (n.d.). Make a little room for the brown-headed nuthatch.

https://nc.audubon.org/conservation/make-little-room-brown-headed-nuthatch - North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. (n.d.). Piedmont habitats.

https://www.ncwildlife.org/wildlife-habitat/habitats/piedmont-habitats - Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency. (2020). Burning for wildlife. https://fwf.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2020/07/Burning-for-wildlife-1.pdf

- University of Maryland Entomology. (n.d.). What is an old field ecosystem? A look from above and below. Entomology. https://entomology.umd.edu/news/what-is-an-old-field-ecosystem-a-look-from-above-and-below

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service. (n.d.). Piedmont series. https://soilseries.sc.egov.usda.gov/OSD_Docs/P/PIEDMONT.html

- USE OF U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (n.d.). USE OF PRESCRIBED FIRE FOR MANAGEMENT OF OLD

FIELDS IN THE NORTHEAST .

https://ecos.fws.gov/ServCat/DownloadFile/132366?Reference=87082