Hiking for Habitat with Luke: The Return of the Yellow-Bellied Sapsucker

In this new blog series, Conservation Coordinator Luke Bennett highlights some of North Carolina’s wild lives and wild places and the ways to enjoy them.

In terms of a grand return, the yellow-bellied sapsucker is on the same level as the Jedi.

In terms of a grand return, the yellow-bellied sapsucker is on the same level as the Jedi.

Just north of downtown Pittsboro, there’s a popular birding hotspot known as Old Bynum Bridge. The bridge has become a chaotic masterpiece, with vibrant graffiti blanketing every surface. At the crack of a warm Sunday dawn, I step out alone onto Old Bynum overlooking the Haw River with fogged-up binoculars in hand. The tree tops are at eye level and already my neck is thankful.

All it takes is one thin sliver of sunlight and the birds respond in a desperate frenzy to refuel and seize the day after a long night of quiet anticipation. As the saying goes, the early bird catches the worm, and those who plan on watching must come equipped with coffee. The graffiti no longer grabs my attention. My eyes zip towards and scan the hardwood trees along the riverbank, which boast a healthy variety of sycamore, sweet gum, black walnut, river birch, maple and oak species, among others.

The birds light up in contrast with the changing leaves and the flowing river. Energetic warblers bounce from limb to limb and escape my feeble attempt to identify each one. Raptors scream and cry as they cruise over the Haw River and land on perches of death. Herons and kingfishers stalk the shallow water below with profound focus. I could write for a lifetime about the diversity of birds on that warm autumn morning. And another lifetime about the dangers facing birds and the haunting thought of a quiet future with little bird activity in the morning.

Half an hour passes until I hear the first drum of a woodpecker. Quickly, I scanned the treetops, searching for what I was sure would be a red-bellied, pileated or downy woodpecker. To my surprise, I noticed a long, solid white wing patch and a striking red crown and throat. A male yellow-bellied sapsucker. The first one I have ever seen, or at least recognized. Back from higher latitudes and now in clear view.

Yellow-bellied sapsucker migratory pattern and habitat

Yellow-bellied sapsucker migratory pattern and habitat

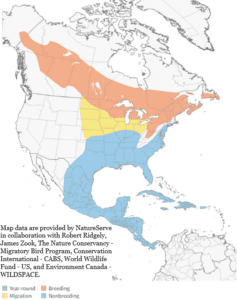

Beginning in September and October, yellow-bellied sapsuckers pack their nonexistent bags and depart their breeding range from the northeastern United States up into Canada and west towards Alaska. Wintering grounds for the sapsucker begin in the southern United States and stretch further south into Mexico, Central America and the West Indies.

As a result of their migratory pattern, North Carolinians typically see yellow-bellied sapsuckers from late September to late April. During this time, they can be found in bottomland hardwood forests up to the high-elevation forests in the North Carolina mountains, but never in pure conifer stands. Sapsuckers prefer young forests with abundant fast-growing trees ripe for sapwells in the spring and summer.

Yellow-bellied sapsucker diet and behavior

The yellow-bellied sapsucker is appropriately named. They feed mainly on tree sap in a manner akin to humans tapping maple trees for maple syrup. In early spring, the sapsucker drills narrow, circular wells into the tree’s xylem, the inner part of the trunk, to feed on sap moving upward toward the branches. After the trees leaf out, the sapsucker creates shallower, rectangular wells in the phloem, the part of the trunk that carries sap down from the leaves. These wells require continual maintenance to keep the sap flowing and sapsuckers tend to drill these wells throughout the year on their breeding and wintering grounds.

Next time you’re on a walk in the woods, keep an eye out for horizontal rows of neatly drilled holes. As you might expect, sapsuckers prefer trees with a high sugar concentration in the sap. They strongly prefer birches and maples but have been observed drilling sapwells in more than one thousand species of trees and woody plants. In addition to sap, sapsuckers eat a variety of insect species and fruit.

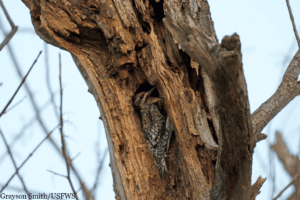

Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are cavity nesters. The trees used for nesting are typically alive but often infected with a fungus that decays the heartwood and makes excavation easier. Excavation takes about 2 to 3 weeks. The entrance hole is normally between 1 and 2 inches, but the cavity itself may be 10 inches deep. The eggs are laid directly on wood chips left over from the excavation. Cavity nests can be reused for several breeding seasons.

Yellow-bellied sapsuckers are cavity nesters. The trees used for nesting are typically alive but often infected with a fungus that decays the heartwood and makes excavation easier. Excavation takes about 2 to 3 weeks. The entrance hole is normally between 1 and 2 inches, but the cavity itself may be 10 inches deep. The eggs are laid directly on wood chips left over from the excavation. Cavity nests can be reused for several breeding seasons.

If you spend enough time observing different woodpeckers, you’ll notice some similar behaviors. Woodpeckers hitch up and down trees while leaning away from the trunk and using their strong tail feathers for support. They fly in a bouncing up-and-down swooping motion. Yellow-bellied sapsuckers in particular, spend most of their time drilling sapwells and slurping up sap and insects. They also spend time foraging for flying insects at the tips of branches or foraging for ants on the ground.

Courting sapsuckers will face each other with bills and tails raised, throat feathers fluffed out and crest feathers raised while swinging their heads from side to side. Interestingly, this is the same behavior displayed between same-sex sapsuckers aggressively facing off. A pair of sapsuckers will typically stay together through the nesting season and often reunite for subsequent breeding seasons to maintain the same nesting area.

Stepping off of Old Bynum Bridge, I’m reminded once again that it is important to stop and listen. It is essential to combat apathy and look a little deeper. And finally, people need to step outside and experience wild places with their own two eyes and their own two feet. You won’t care about it if you don’t know it’s there. North Carolina is a global biodiversity hotspot. Let’s keep it that way.

Source – The Cornell Lab of Ornithology