What Chronic Wasting Disease Means for NC Deer and Hunters

It’s Here: Chronic Wasting Disease has been detected in North Carolina. Here’s what that means for deer—and for deer hunters.

Article written by Robert D. Brown, Ph.D. and Liz Rutledge, Ph.D. and originally appeared in NCWF’s Summer Journal. Brown is former department head and dean at Mississippi State University, Texas A&M, and NCSU; past president of The Wildlife Society; and a current NCWF board member. Rutledge is a certified wildlife biologist, NCWF’s director of wildlife resources, and president of NC Hunters for the Hungry.

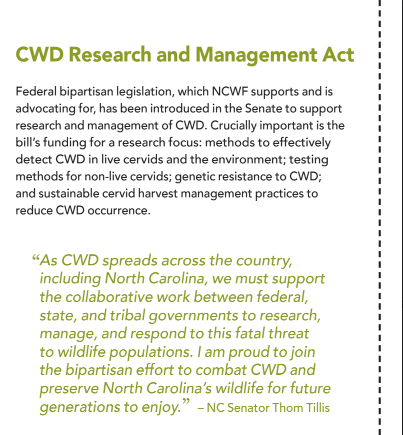

There is a new disease in our state. It’s transmitted from individual to individual, with no treatment or cure, and it is 100 percent fatal to cervids. It’s chronic wasting disease (CWD) and it infects species including white-tailed deer, mule deer, elk, and moose. Since 1999, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC) has tested more than 22,000 deer from road kills, taxidermists, meat processors, and hunters. All samples were negative for CWD prior to March of this year. On March 31, 2022, CWD was detected in a sample submitted for testing by a taxidermist from a deer harvested in December of 2021 from northern Yadkin County. This positive result was the first case of CWD detected in North Carolina’s deer herd and was confirmed by the National Veterinary Services Laboratory in Ames, Iowa. On April 12, 2022, NCWRC Director Cameron Ingram invoked “Emergency Powers” to put the state’s CWD Response Plan into action in collaboration with the N.C. Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (NCDACS).

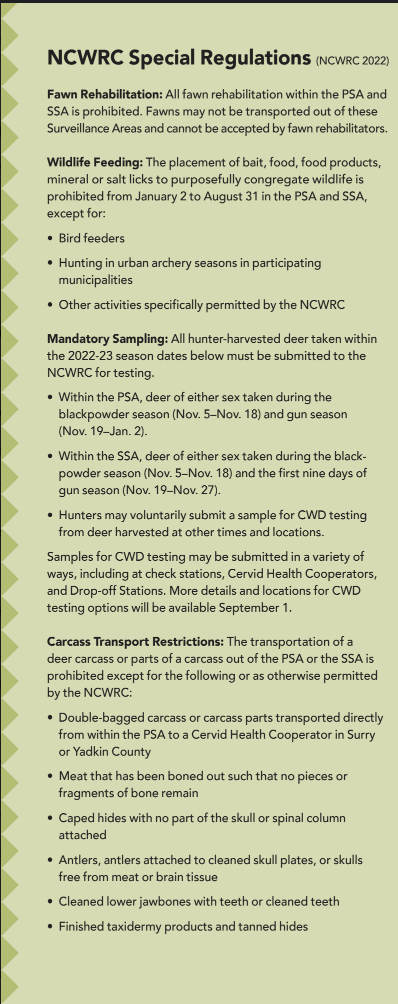

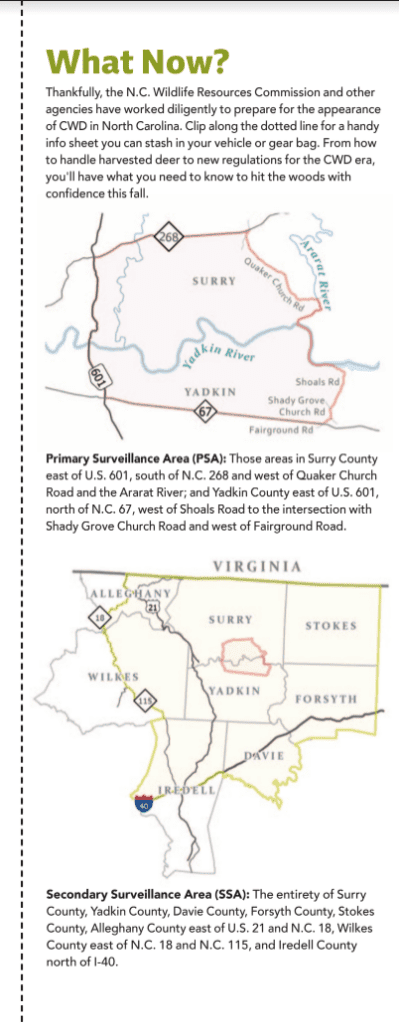

In response to CWD in North Carolina, NCWRC established Primary and Secondary Surveillance Areas in parts of Surry, Yadkin, Davie, Forsyth, Stokes, Iredell, and Alleghany Counties to increase surveillance efforts to detect any additional cases of CWD in white-tailed deer. NCWRC developed a Cervid Health Cooperator Program, including taxidermists, meat processors, and stand-alone cooler sites around the state, so that hunters can deposit their hunter-harvested deer heads for CWD testing, free-of-charge. Fortunately, our state recognizes the need for in-state CWD testing to ensure all laboratory work is carried out efficiently, and test results can be conveyed to hunters in a timely manner. Therefore, in the future, some CWD testing will occur at the new Troxler Agriculture Center in Raleigh.

Origination and Spread of CWD

CWD is an insidious disease. It is believed to have originated in deer and elk at a research facility at Colorado State University in 1967. The deer and elk were likely infected by sheep in an adjacent pen that had scrapie, a similar disease. The disease “jumped” species, and when the asymptomatic deer and elk were sent to facilities in other states, the disease began to spread among penned and wild cervids. The first case of CWD in a wild cervid was detected in an elk in Colorado in 1981. The disease has now been detected in 30 states and the transfer of cervids among breeding facilities and game farms has exacerbated the spread of the disease to free-ranging individuals across the country. Infected deer in farming operation facilities have escaped on occasion, may have nose-to-nose contact with wild deer at pens lacking double fencing, or be unknowingly transferred to other locations.

CWD was found in Saskatchewan in Canada and thought to have originated from a game farm in South Dakota. That Canadian game farm sent animals to 40 other facilities, and 21 of those eventually detected CWD. After officially closing its borders to cervid importation 10 years earlier, Texas detected CWD on a game farm (possibly brought in from illegally transported deer) which had shipped deer to 46 counties in the state. CWD has been detected in deer as far away as Norway and Korea–from deer shipped from Colorado and Wyoming. NCWF has adamantly opposed deer farming in North Carolina; however, the deer farms that currently exist are monitored closely under the purview of NCDACS. Thanks to advocacy efforts, there is an importation ban.

How Does CWD Impact Cervids?

CWD is a self-replicating, misfolded protein—not a parasite, bacterium, or a virus—that contains no genetic material. CWD belongs to the family of diseases called transmissible spongiform encephalopathies, and causes infected tissue associated with the nervous system to form a sponge-like appearance. It is similar to scrapie in sheep and mad cow disease in cattle, as well as to a similar disease in mink, and Kuru and Creutzfeldt-Jacob disease in humans. To date, there have been no occurrences of CWD in humans; however, mad cow disease was found in humans in England and 229 people died as a result.

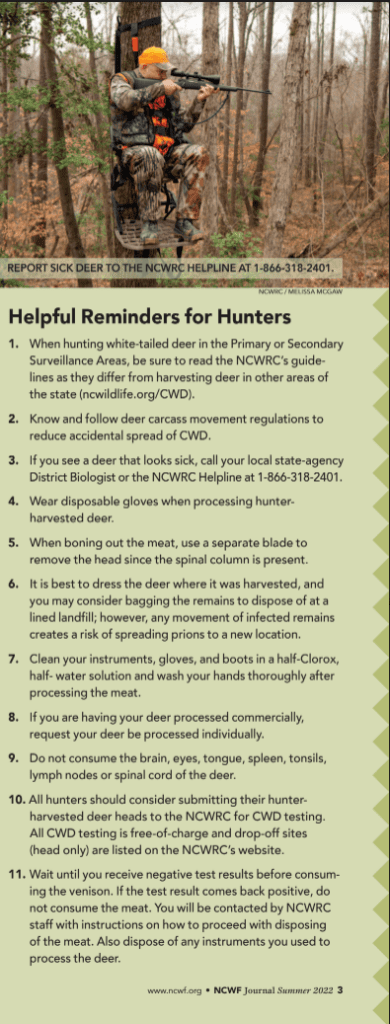

Part of the difficulty in managing CWD is that its incubation period averages 18-24 months between initial infection and the presence of visible signs. During the incubation period the disease can spread to other individuals virtually undetected. Testing is imperative because it’s nearly impossible to tell if a deer has CWD by observation unless the CWD is in a very progressed form. The signs of CWD in cervids, after progression of the disease, include poor body condition, stumbling, and changes in behavior (such as reduced fear of humans), excessive drooling, difficulty swallowing, and excessive urination and thirst.

The infection is primarily found in the brain, spinal cord, eyes, lymph nodes and spleen, but can also be found in urine, feces, blood, saliva, and deboned meat. It can be transmitted from one deer to another, mother to offspring, from cervids to soil and plants, and from soil and plants back to cervids. Plants can take up CWD prions in the soil through their root systems and once present, CWD prions cannot be destroyed by disinfectants, alcohol, formaldehyde, detergents, freezing, radiation, desiccation, protein enzymes or incineration at 1,100 degrees F (enough to melt aluminum).

Male deer have three times the rate of infection as does, most likely due to behavior during breeding and fighting–and thus more contact with other deer. On a positive note, CWD has not been detected in North Carolina’s elk population; however, to keep CWD at bay, wildlife managers, conservation groups, hunters, and meat processors will need to remain vigilant and follow all state-issued regulations regarding CWD to protect the state’s population of approximately 250 individuals. The effect of CWD on cervid populations, hunters and wildlife agencies can be tragic once introduced; however, stringent management can reduce the impacts.

Personal Consumption of Meat and Feeding the Hungry

Currently, there is no evidence of transmission of CWD from cervids to humans through the consumption of hunter-harvested venison and hunting will be a vital management tool used to survey for spread of the disease. It has been estimated that hunters and their families consume venison from 7,000 to 15,000 CWD infected deer annually and none of those individuals has contracted the disease.

Testing of hunter-harvested deer is an important tool for consumers and networks that provide processed venison for the hungry, underscoring the need for funding and for research into an effective live test. North Carolina is new to the list of states with positive cases of CWD; however, most previously infected states have continued to harvest cervids for human consumption. In North Carolina, NCWRC proactively banned the use of commercial products containing any bodily excretions from cervids, without specific certification, for taking or attracting wildlife due to the potential for the spread of CWD, which was strongly supported by NCWF.

CWD’s Potential Economic Impact to Wildlife Conservation

After the first three cases of CWD in wild deer were found in Wisconsin in 2002, hunting license sales dropped by 90,000, and the state’s Department of Natural Resources lost $3 million from the loss of license fees and federal Pittman-Robertson matching funds. Wisconsin lost over $50 million from the loss of equipment sales, food and lodging sales and other hunting-related expenses. In addition, the state spent $25 million a year from 20022006 on CWD-related control efforts. Other states have seen similar losses, and they continue. These figures are dramatic; fortunately, the NCWRC has implemented an effective Response Plan and tested over 7,200 hunter-harvested deer from the 2021-2022 hunting season alone, resulting in only one positive case.

What will happen to North Carolina’s white-tailed deer and elk populations remains to be seen; however, with diligent work and continued testing, and future research, the hope is NCWRC’s current CWD Response Plan will keep the disease as isolated as possible. If spread continues to occur, there will likely be additional regulations involving transport of live deer among breeding facilities, transport of carcasses, baiting and feeding of wild deer, and hunter harvest and testing.

Continued partnership and cooperation between state agencies, conservation groups, and the public on awareness, education, and management of CWD will give North Carolina the best hope of minimizing the spread of this devastating disease. NCWF will provide our full support to the NCWRC as it will take us all, including hunters, processors, researchers, and wildlife advocates, to combat this disease. In addition, the science is moving forward daily to help increase knowledge of the disease and improve management strategies. NCWF advocates for awareness and education as our state focuses resources and management efforts toward this disease and encourages all hunters to continue enjoying outdoor recreation and consumption of wild game in a responsible and pragmatic manner.

Read more

Localized Overpopulation of Deer Hurts Herds and Ecosystem

First CWD-Positive Deer in North Carolina; Emergency Response Plan Initiated