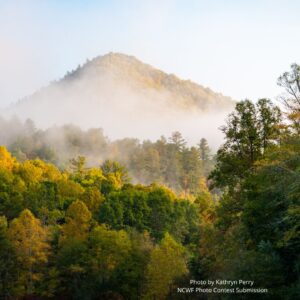

The North Carolina Mountains and Their Wildlife

What is the Mountain Region?

The Mountain region of North Carolina encompasses 23 counties in the western part of the state. This area, part of the Appalachian mountain range, showcases a diverse landscape of mountains and valleys. The terrain shifts dramatically at the Blue Ridge escarpment, an abrupt and steep slope that creates the distinctive blue wall visible when approaching the mountains from the east. This escarpment also serves as a vantage point for many overlooks along the Blue Ridge Parkway north of Asheville (Blevins and Schaffale). Mount Mitchell is the tallest mountain in the state and the highest peak east of the Mississippi, rising to 6,684 feet above sea level. Due to its high elevation, Mount Mitchell shares flora and fauna with Canadian forests (Martin).

The Mountain region of North Carolina encompasses 23 counties in the western part of the state. This area, part of the Appalachian mountain range, showcases a diverse landscape of mountains and valleys. The terrain shifts dramatically at the Blue Ridge escarpment, an abrupt and steep slope that creates the distinctive blue wall visible when approaching the mountains from the east. This escarpment also serves as a vantage point for many overlooks along the Blue Ridge Parkway north of Asheville (Blevins and Schaffale). Mount Mitchell is the tallest mountain in the state and the highest peak east of the Mississippi, rising to 6,684 feet above sea level. Due to its high elevation, Mount Mitchell shares flora and fauna with Canadian forests (Martin).

The Appalachian mountains were shaped over hundreds of millions of years by volcanic and tectonic forces, with a significant event occurring during the formation of Pangaea when the North American and European-African continents collided, resulting in tectonic uplift that elevated the range (USGS). This makes the Appalachian Mountains the oldest mountain range in North America and one of the oldest in the world. The age contrast with the Rocky Mountains is evident, as millennia of erosion, weathering, and glaciation have softened the cliffs and peaks of the southeastern mountains, giving them a more rounded appearance compared to the younger, rugged Rocky Mountains (Britannica).

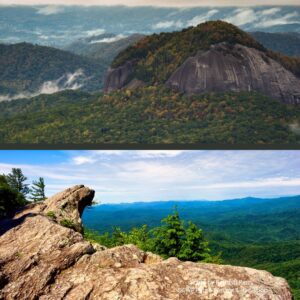

In many parts of North Carolina’s mountains, the underlying geology primarily consists of hard metamorphic and igneous rocks such as granite, schists, gneisses, slates, and quartzites. For example, Blowing Rock is mainly composed of gneiss, while Looking Glass Rock features granite formed from molten rock that cooled underground (Our State). Over millennia, the weathering of these formations combined with the decay of plant life has resulted in several feet of soil over layers of saprolite, often referred to as “rotten rock”. This saprolite is created by

Looking Glass Rock (top) and Blowing Rock (bottom)

the breakdown of feldspars and micas due to chemical weathering from moisture and natural acids seeping through the topsoil. The prevalence of this process means that rocky outcrops appear only in areas where the rock is particularly resistant to weathering (Blevins and Schafale).

The combination of rocky outcrops, fertile soil, diverse topography, and shallow hardpan fosters unique ecological communities throughout the North Carolina Mountain region. These include mountain cove forests, spruce-fir forests, mountain bogs, grassy balds, mountain streams, and more.

Mountain cove forests are perhaps one of the most recognizable ecotypes in the landscape. According to North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission (NCWRC), mountain cove forests “occur on sheltered, moist, low to moderate elevation sites. They are characterized by a dense forest canopy of moisture-loving trees.” Also, 18th century naturalist William Bartram, inspirationally noted on his awestruck journey into a mountain cove, “We… mounted their steep ascents, rising gradually by ridges or steps one above another, frequently crossing narrow, fertile dales as we ascended; the air feels cool and animating, being charged with the fragrant breath of the mountain beauties, the blooming mountain cluster Rose, blushing Rhododendron and fair Lily of the valley.”

Wildlife in the Mountains

William Bartram was among the first to observe the absence of buffalo and elk in their historic grazing grounds in North Carolina, attributing this to extensive overhunting. He remarked, “the buffaloe, once so very numerous, is not at this day to be seen in this part of the country” (Martin).

Photo by Deborah Roy of Charlotte, NCWF Photo Contest Submission

Thanks to reintroduction efforts by the NCWRC, the National Park Service, and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, elk populations in the state have grown to nearly 275, though they still face challenges from elk-vehicle collisions, habitat loss from development, and the potential threat of chronic wasting disease.

The mountain region is also rich in biodiversity. The Appalachian mountains have largely escaped desertification and glaciation over the millennia (Martin). Coupled with a temperate climate, ample rainfall, and diverse ecological communities, this area provides a stable environment for long-term inhabitants, including unique salamander species found nowhere else on Earth.

The region’s deep valleys and high peaks create barriers that restrict some species’ movements, resulting in isolated ecological communities. This isolation has led to significant adaptations among certain species, such as the arboreal Hickory Nut Gorge salamander, which is endemic to the region. Growing up to two feet long and weighing up to three pounds, the eastern hellbender is also a mountain stream resident in North Carolina. These mountain salamanders play a crucial role in making the state home to the greatest diversity of salamanders globally.

Salamanders are not the only wildlife that thrives in the North Carolina mountains. Reverend Moses Ashley Curtis and Ebenezer Emmons

observed that the state’s rich plant and animal diversity is largely due to its geographical position, where northern and southern species converge. This is particularly evident in the mountain region, which better supports many northern species compared to the warmer, flatter areas of the state (Martin, 9).

North Carolina’s natural landscapes have suffered from overdevelopment, deforestation,

and environmental degradation. While the mountain region has largely resisted the scale of development seen in the Piedmont, but it does still face threats at the hands of development. As early as 1908, Secretary of State Joseph E. Pogue noted that 86 percent of southern Appalachian land was either cleared of trees, in various stages of regrowth, or covered in young second-growth forests (Peters). This land clearing remains a significant threat in certain areas of the NC mountain region, particularly the loss of mature and old-growth forests, which many wildlife species depend on.

Recently, NCWF and The National Wildlife Federation expressed support for the US Forest Service’s National Old Growth Amendment, which aims to enhance protection and management for the state’s old-growth forests, particularly in the mountain region.

Carolina Northern Flying Squirrel (Glaucomys sabrinus)

Carolina northern flying squirrel, photo by NCWRC

The Carolina northern flying squirrel is one of two flying squirrel species found in North Carolina. Its relative, the southern flying squirrel, prefers lower elevations, while the Carolina northern flying squirrel inhabits higher altitudes, typically between 4,000 and 5,000 feet above sea level. This species primarily feeds on lichens, mushrooms, seeds, and nuts.

Due to its high-elevation habitat and nocturnal habits, the Carolina northern flying squirrel tends to remain hidden from human observation. In fact, it went largely unnoticed until it was discovered in the 1950s. It was listed as endangered in 1985, just 35 years later, primarily due to deforestation and forest fires that destroyed essential habitats. The introduction of invasive species, such as the balsam and hemlock woolly adelgids, has further harmed balsam fir and hemlock trees, forcing the squirrels to rely on less suitable tree species.

This squirrel can be found in various locations across North Carolina, including Long Hope Mountain, Roan Mountain, Grandfather Mountain, Unaka Mountain, the Black-Craggy Mountains north and east of the French Broad River Basin, as well as the Great Balsam, Plott Balsam, Smoky, and Unicoi Mountains to the south and west of the basin.

NCWF’s Old-growth Forest Work

Since 1945, the North Carolina Wildlife Federation has been dedicated to the protection, conservation, and restoration of wildlife and their habitats, with old-growth forests being a crucial habitat type for species like the brown-headed nuthatch.

In August of this year, NCWF Vice President of Conservation Policy Manley Fuller published an Op-Ed expressing support for the US Forest Service’s National Old Growth Amendment, which aims to safeguard and manage mature and old-growth forests for both people and wildlife.

Carolina northern flying squirrels cannot nest in small trees that lack the size or age necessary to form cavities. These mature forest ecosystems provide essential cavity nesting sites for brown-headed nuthatches and other wildlife.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- You can learn more about the Carolina northern flying squirrel, other endangered species, and old-growth forests they depend upon at the below links:

What You May Not Know About NC’s Five Squirrel Species

Act:

- Express support for policies that promote the effective management and protection of mature and old-growth forests, benefiting Carolina northern flying squirrels and other species that rely on mature trees for nesting habitat.

- Whenever possible, leave dead trees, or snags, standing, as they offer valuable nesting sites for various wildlife species, including both Carolina northern and southern flying squirrels.

Bog Turtles (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)

“Bog Turtle” by USFWS Headquarters

The southern bog turtle holds the title of the smallest turtle in North America, growing to less than five inches in length—about the size of a human palm. This species features distinctive coloration, predominantly dark with a splotchy yellow band encircling its neck.

Bog turtles are specialized habitat dwellers, relying on mountain bogs for survival. The thick moss, muck, and small patches of vegetation in these groundwater-fed wetlands provide ideal conditions for seeking cover from predators, basking in the sun, and foraging for food. As an omnivorous species, their diet includes plants, worms, insects, and snails.

In the wild, bog turtles typically live to around 10 years, but in protected environments, they can reach ages of up to 60 years.

Currently listed as threatened, there are only about 100 populations across 24 counties in western North Carolina. Their decline is largely due to the loss of bog habitats that are essential for their survival.

Bog turtles inhabit small, grassy wetlands, spring-fed areas with minimal canopy, and riparian systems often near pastures. These habitat characteristics require the implementation of prescribed grazing, which keeps the canopy open and softens the soils that the bog turtle calls home. About 75% of their Southeastern habitat is on private land, making collaboration with landowners essential for conservation. Project Bog Turtle, a North Carolina Herpetological Society initiative, engages state, federal, and private partners in surveys, population studies, and habitat restoration. Effective management is crucial, as bog turtles are confined to small mountain bogs that can be overgrown without active maintenance. Current efforts to keep these areas open are vital for the species’ conservation. Find out more in the NCWRC Wildlife Action Plan.

White v. Environmental Protection Agency – Fighting for Wetlands Protections

Attorneys for NCWF and National Wildlife Federation have filed a motion in the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina to intervene in White v. EPA. This case challenges federal protections for wetlands, greatly reduced by the 2023 Sackett v. EPA federal Supreme Court decision. The plaintiff argues for a narrow definition that could exclude most wetlands from Clean Water Act coverage, endangering the benefits these habitats provide to people, outdoor enthusiasts, and communities. Mark Sabath of the Southern Environmental Law Center warns that such a ruling could devastate North Carolina’s waters and beyond, affecting drinking water, wildlife, fisheries, and flood protection.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- You can learn more about bog turtles and wetlands conservation in North Carolina through these links below:

Everything You Need to Know About NC Wetlands

A Call from the Top – Gov. Cooper’s Executive Order provides critical roadmap for NC wetlands

Act:

- Understand the vital role wetlands play for wildlife, people, and the environment.

Brook Trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)

“Brook Trout–NPS Photo” by Great Smoky Mountains National Park

Brook trout belong to the char family. While brown trout, rainbow trout, and brook trout can all be found in certain mountain streams and lakes, brook trout are the only species native to North Carolina. Despite this, many brook trout—along with brown and rainbow trout—are stocked by fisheries in delayed harvest streams to enhance recreational fishing opportunities.

Native brook trout are typically found in small, high-altitude headwaters and streams in North Carolina’s mountains, classified as Southern Appalachian brook trout. Although there are various types of brook trout, they all share a muted gray-green base color adorned with vibrant gold, white, and orange speckles. While stocked brook trout can grow to lengths of one to two feet, native brook trout generally reach only six to eight inches.

The challenges facing brook trout are common to many species within the mountain stream ecosystem. These include sediment and chemical runoff from nearby agricultural practices, extreme flooding and drought cycles, species competition, and rising water temperatures that can be harmful to trout.

NCWF’s Trout Buffer Work

NCWF is advocating for the passage of Senate Bill S613, the most basic of conservation measures aimed at safeguarding trout streams from pollution and sediment runoff, which is currently stalled in the state House of Representatives.

This proposed legislation would ensure a nominal buffer zone of 25 feet for new agriculture activities along the banks of North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality designated trout waters. This change would institute streamside buffers for new agricultural activities. The North Carolina Sedimentation Control Act regulates streamside forestry operations subject to best management practices and development along streams is also subject to the act’s requirements.

What You Can Do To Help

Learn:

- You can learn more about brook trout and mountain stream ecosystems through these resources:

The Ins and Outs of NC Delayed Trout Harvest

A Deep Dive into 5+ NC Ecological Communities and the Wildlife Within Them

Trout Waters Fact Sheet S613 – North Carolina Wildlife Federation

Act:

- Practice ethical recreational fishing, and follow regulations posted by the NCWRC.

- Be mindful of development and agricultural practices in close proximity to streams, and the detrimental effects that these projects may have on wildlife and water quality.

Written by:

– Bates Whitaker, NCWF Communications & Marketing Manager

– Dr. Liz Rutledge, NCWF VP of Wildlife Resources

Sources:

- Bledsoe, M. (2021, July 1). Written in stone: North Carolina’s rock formations. Our State.

https://www.ourstate.com/written-in-stone-north-carolinas-rock-formations - Blevins, D., & Schafale, M. P. (2011). Wild North Carolina: Discovering the wonders of our state’s natural communities. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2024). Plant and animal life. In Appalachian Mountains.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Appalachian-Mountains/Plant-and-animal-life - Martin, M. (2001). A long look at nature: The North Carolina State Museum of Natural Sciences. The University of North Carolina Press.

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. (n.d.). Cove forests.

https://www.ncwildlife.org/cove-forests-444pdf/open - Peters, G. (2021) Our National Forests: Stories from America’s Most Important Public Lands. Timber Press.

- U.S. Geological Survey. (n.d.). What was Pangea?

https://www.usgs.gov/faqs/what-was-pangea