Spotlight on Seven Species for National Wildlife Day, Sept. 4

National Wildlife Day is Sept. 4

“The wildlife and its habitat cannot speak, so we must and we will.”

Theodore Roosevelt

North Carolina is perhaps the most ecologically unique state in the southeast, mainly due to its borders’ three distinct biomes: Coastal, Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains. In celebration of National Wildlife Day on Sept. 4, we’re highlighting the importance of habitat and biodiversity and a few of our favorite species – some of which you may see or hear this month.

1. Bog turtle (Glyptemys muhlenbergii)

One of the unique treasures found in some North Carolina mountain bogs is the threatened bog turtle, the rarest and smallest turtle in North America. Bog turtles reside in wetlands along the Appalachian Mountains into the Blue Ridge Escarpment and parts of the Piedmont. They mate from about March to June, lay eggs in June and July, and hibernate from October to April. In September, their nests are hatching in the mountains and foothills.

Bog turtles were placed under federal protection in 1997 in response to an 80-percent population reduction compared to historical numbers. These reptiles have been threatened over the years by loss or fragmentation of habitat due to agriculture, invasive species, the succession of habitat and land development. Actions to help this species include captive breeding programs, controlled burns, responsible land development, and managed cow grazing. LEARN MORE

2. Elk (Cervus elaphus manitobensis)

In September, bull elk are bugling in Cataloochee Valley – an impressive and unmistakable sonic display absent from North Carolina for years. Many are surprised to learn that more than 200 wild elk currently roam their historic eastern range in the mountains of North Carolina. The triumphant return of this majestic animal to the Southern Appalachians is nothing short of a wildlife success story and one that’s still being written today.

Fragmentation, loss of suitable habitat and increased vehicles on roads are all ongoing threats to growing the current elk population. As urban and suburban development continues and vehicle traffic increases, it’s vital to prioritize connectivity for wildlife like elk to traverse roadways safely. These measures help animals fulfill their biological needs and reduce the risk to drivers associated with wildlife-vehicle collisions. LEARN MORE

3. Monarch butterfly (Danaus plexippus)

September is usually great for butterfly-watching, especially along the Blue Ridge Parkway and Tunnel Gap. With their striking orange, black and white patterned wings fluttering across Carolina blue skies, monarch butterflies perform a magical show. And North Carolinians are lucky to have a front-row seat to this kaleidoscope of natural beauty this month.

Monarchs fly from spring to fall and typically have 4-5 generations, with the last generation making the great migration back to its overwintering grounds in Mexico. They and other pollinators have been severely declining due to habitat loss, misuse of pesticides and climate change. Like other pollinators, monarch butterflies rely on a single group of plants for reproduction, milkweed (Asclepias spp.).

Native pollinator plants expand other species’ reproduction potential and increase foraging opportunities. Pollinators benefit from diverse pollen sources and nectar as it improves nutrition and increases disease and parasite tolerance. LEARN MORE

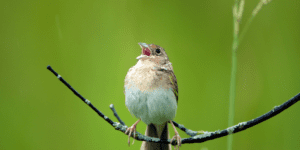

4. Grasshopper sparrow (Ammodramus savannarum)

This small, short-tailed sparrow winters from the southern U.S. to Costa Rica and the Caribbean and is a breeding summer resident of open native grasslands, fields, and prairies in much of the eastern United States and Great Plains.

In North Carolina, this ground-nester can be found in the Blue Ridge Mountains, Piedmont and coastal plain, where it builds a nest in a slight depression at the base of a clump of grass. Its name comes from a buzzy song and the preference for grasshoppers, which it paralyzes with a pinch to the thorax and then methodically shakes off each pair of legs before feeding the prey to its young. LEARN MORE

5. Northern bobwhite (Colinus virginianus)

This common gallinaceous (chicken-like) gamebird, also known as the quail, is a permanent resident of overgrown fields and open woodlands such as longleaf pine stands in much of the eastern United States, Great Plains and the Southwest. In the winter, quail can be found in coveys of more than 20 birds. They typically roost in a circle with their heads positioned outward.

In North Carolina, this ground-nester can be found throughout the state and builds a nest in a grass-lined hollow with up to 20 white eggs. The chunky quail gets its name from its loud and piercing whistle and feeds on seeds, small succulent leaves, and insects, including grasshoppers, beetles and cutworms. LEARN MORE

6. Marbled salamander (Ambystoma opacum)

This boldly patterned salamander was adopted as North Carolina’s official state salamander in 2013. Marbled salamander habitat includes moist woodlands near swamps, ponds or other wetland areas. Rarely seen because of their nocturnal habits, marbled salamanders have begun moving to their breeding sites on rainy nights. Notably different from salamanders in the same family, the marbled salamander breeds on land in the fall rather than in water during spring.

Males usually move in first. Females deposit their eggs under sheltering objects or surface litter on land in or along dry woodland pools, attending them until winter rains inundate the collections and hatch the eggs. This provides them a head-start on most winter-breeding amphibians. Marbled salamanders are more tolerant of dry habitats because they create burrows under logs, leaf litter, or underground, a behavior that is uncommon in other salamander species. LEARN MORE

7. Brook trout (Salvelinus fontinalis)

Brook trout inhabit headwater streams in our western mountains that provide the cool, clear, well-oxygenated waters the species requires to reproduce and grow. Technically, the brook trout is not really a trout but rather a char more closely related to dolly varden and Arctic char than rainbow and brown trout. Still, it is considered the only trout native to North Carolina.

The original strain of brook trout in North Carolina is the southern Appalachian trout, genetically distinct from its northern cousins that initially ranged from the mid-Atlantic states to Canada. Widespread stocking of northern strain fish – which occurred before we knew a specific native strain – eliminated many southern Appalachian strain populations.

Today, some of our brook trout waters contain only northern fish, some have mixed populations, and some continue to support southern Appalachian populations. In 2005 the General Assembly designated Southern Appalachian brook trout as North Carolina’s official freshwater trout. LEARN MORE